I promised I would not usurp this blog for off-topic book reviews. The last post was indeed a book review, but very much on-topic. Here I post a brief extract from my latest review (Dombey & Son), which again is on-topic. One of the foundations of the feminist mindset is a distorted view of history as unrelenting oppression of women. Academic history is poor at exposing the nature of intimate relations in the past. Even so-called social histories tend to be written on a large scale, not the personal scale. So, perhaps the best guide to the relations between the sexes in the past can be found in novels, which have the advantage of focusing on the personal and the intimate. That novels are, obviously, works of fiction is not as significant an objection as it might first appear. Authors would deploy character types which their audience would readily recognise. That Lady Catherine de Bourgh did not exist outside the pages of Pride & Prejudice is irrelevant to the accuracy of her depiction as representative of a type of powerful dowager of whom readers of the time would be able to think of real-life examples. Dickens’ Dombey & Son is particularly illustrative as its main theme is Mr Dombey’s appalling distain for his daughter in favour of his son, so ostensibly a novel which might appeal to feminists – except that the reader is clearly expected to find Mr Dombey monstrously unnatural. However…. here is an extract involving two minor characters which gives us an insight into the historical realities of what we would now call domestic abuse.

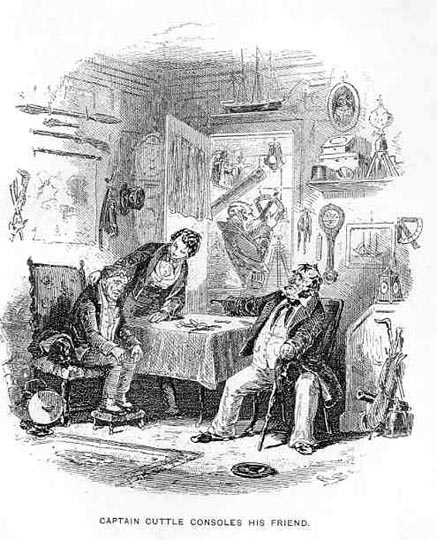

Captain Cuttle and Jack Bunsby

Captain Cuttle, retired old sea Captain, is one of those irresistibly endearing Dickens characters, as simple as he is staunch, the salt of the earth – or, rather, a salt of the sea in this case. Here is Dickens’ description, “No child could have surpassed Captain Cuttle in inexperience of everything but wind and weather, in simplicity, credulity, and generous trustfulness. Faith, hope and charity shared his whole nature among them.”

The Captain’s difficulties with his landlady, the termagant Mrs MacStinger, is an object lesson in domestic abuse, illustrating that there is no need for any intimate relationship for this term to apply. Captain Cuttle was, simply put, terrified of Mrs MacStinger who had a hold over him that we can understand as coercive control. The Victorians clearly had no trouble recognising the phenomenon, though perhaps no specific term for it. At one point we read the Captain explaining his recent absence, saying: “‘We had some words about the swabbing of these here planks, an she – in short’, said the Captain, eyeing the door and relieving himself with a long breath, ‘she stopped my liberty.’”

The Captain’s flight from the abusive Mrs MacStinger did not relieve him of this fear. Rather, now lodging in old Sol Gay’s shop, he remained fearful whenever he ventured out, in case he should run into her. “The Captain never dreamed that in the event of his being pounced upon by Mrs MacStinger, in his walks, it would be possible to offer resistance. He felt it could not be done. He saw himself, in his mind’s eye, put meekly in a hackney-coach, and carried off to his old lodgings. He foresaw that, once immured there, he was a lost man: his hat gone; Mrs MacStinger watchful of him day and night.” How much clearer could a case of coercive control possibly be?

Captain Cuttle’s greatly respected friend Bunsby also suffered under the hand of a controlling landlady, and we intuit that Dickens must have had some first-hand experience of the breed. Relating to Bunsby’s removal of the gangway which led to his dwelling on a boat, we read: “That the great Bunsby, like himself (Cuttle), was cruelly treated by his landlady, and that when her usage of him for the time being was so hard that he could bear it no longer, he set this gulf between them as a last resource.”

Alas, poor Bunsby. Having had the goodness to retrieve the Captain’s trunk from his previous dwelling with Mrs MacStinger, Bunsby becomes ensnared as her next victim.

The main theme of Dombey & Son may be quasi-feminist, but Dickens repeatedly reminds us throughout the book that, not only is this an aberrant behaviour specific to Mr Dombey but, if any more widely characteristic of popular sentiment, is confined to the bourgeoisie. The lower orders, we are reminded at many points, experienced very different conditions as regards relations between the sexes. So, the feminists do not get this story all their own way.

In a scene towards the end, Captain Cuttle runs across his old friend Jack Bunsby now securely captured by Mrs MacStinger. They are on their way to church to be wed. Captain Cuttle is justifiably alarmed, not least because Bunsby’s demeanour does not speak of voluntary action. Here they are nearing the altar,

“‘Jack Bunsby,’ whispered the Captain, ‘do you do this here of you own free will?’

Mr Bunsby answered, ‘No’.

‘Why do you do it, then, my lad?’ inquired the Captain, not unnaturally.

Bunsby, still looking, and always looking with an immovable countenance, at the opposite side of the world, made no reply.

‘Why not sheer off?’ said the Captain.

‘Eh?’ whispered Bunsby, with a momentary gleam of hope.

‘Sheer off’, said the Captain.

‘Where’s the good?’, retorted the forlorn sage. ‘She’d capter me agen’.

‘Try!’ replied the Captain. ‘Cheer up! Come! Now’s your time. Sheer off, Jack Bunsby.’

Mr Bunsby merely uttered a suppressed groan.

‘Come!’ said the Captain, nudging him with his elbow, ‘now’s your time! Sheer off! I’ll cover your retreat. The time’s a flying. Bunsby! It’s for liberty. Will you once?’

Bunsby was immovable.

‘Bunsby!’ whispered the Captain, ‘will you twice?’

Bunsby wouldn’t twice.

‘Bunsby!’ urged the Captain, ‘it’s for liberty; will you three times? Now or never!’

Bunsby didn’t then, and didn’t ever; for Mrs MacStinger immediately afterwards married him.

One of the most frightful circumstances of the ceremony to the Captain, was the deadly interest exhibited therein by Juliana MacStinger; and the fatal concentration of her faculties, with which that promising child, already the image of her parent, observed the whole proceedings. The Captain saw in this a succession of man-traps stretching out infinitely; a series of ages of oppression and coercion, through which the seafaring line was doomed.”