Quoting from the web site of the Drive Project, “Drive is an intensive intervention that works with high-harm and serial perpetrators to challenge behaviour and prevent abuse. A few years ago I wrote a review of domestic abuse perpetrator programmes, UK DV Perpetrator Programmes – Part 1. Drive is a new one. In December 2019, the University of Bristol published their evaluation of a three-year pilot of Drive. This 189 page evaluation, led by Marianne Hester, can be found here, with a executive summary here. It is claimed to be, “the largest evaluation of a perpetrator intervention ever carried out in the UK, and the largest with a randomised control design”. In this article I deconstruct this evaluation.

I hope the reader will be patient as it is necessary to go into details. Documents of this sort are cleverly scripted. Penetrating the façade to expose the reality beneath requires some labour. Let me give you the punchline: the claimed benefits of Drive are fraudulent.

This article is structured as follows,

- The subjects of the Drive pilot;

- An outline of the Drive process;

- The structure of the Drive pilot;

- A summary of the evaluation’s key claims for the benefits of Drive;

- My critical appraisal of these claims, addressing,

- Assessed changes in victimisation;

- Assessed changes in perpetrator behaviour;

- Repeat MARAC* evidence;

- Police data evidence.

- Drive-DASH Changes

- Cost of Drive

- Conclusions

*MARAC = Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference, the mechanism whereby all relevant agencies such as police, social services, DV experts, etc., come together to discuss a case and agree action.

The Subjects of the Drive Pilot

- 94% of the perpetrators were men.

- 97% of the victims were women.

The evaluation is based upon the presumption that there is a clear and unambiguous division of these couples into a perpetrator and a victim. Statistically this is unlikely. In many cases both parties will have been comparably abusive, but this is a reality which is not allowed to surface in the Drive process or its evaluation. In some cases it might even be that the victim and perpetrator have been reversed.

The designated perpetrators in the pilot were not a random cross-section of the public by any stretch of the imagination. Their characteristics were (using the terminology of the evaluation),

- 62% had high or excessive mental health issues

- 40% were temporarily homeless or sofa surfing, plus another 7% actually homeless

- 34% had high or excessive alcohol usage

- 28% had high or excessive drug use

- 21% had planned or attempted suicide

- Where contact was made with the service user, 61% had financial difficulties, 43% employment difficulties, and 62% poor physical health.

The DRIVE Process

The Drive process is driven by “case managers”. Who these “case managers” are, and what their affiliations might be, was not specified.

The important thing to grasp is that Drive is predominantly NOT about working with the perpetrator; it is predominantly about multi-agency working without perpetrator involvement. It implements a system of surveillance (referred to as “disruption”).

The Drive process is described thus,

“Drive focuses on reducing harm and increasing victim safety by combining disruption, diversionary support and behaviour change interventions alongside the crucial protective work of victims’ services.”

The Drive process divides into “direct” and “indirect” work, the latter does not involve the perpetrator’s involvement with the case manager.

Direct work comprises what is denoted above as “diversionary support and behaviour change interventions”. This is billed as a bespoke service, driven by the case manager according to the needs of the service user (perpetrator). As such it is a mixture of things whose purpose is to change the perpetrator’s behaviour, e.g.,

“Case managers threaded a delicate balance between building trust, setting boundaries and critically challenging service users. The effectiveness of this hinged on the quality of the case manager-service user relationship, the presence of meaningful levers to engage (e.g., forms of statutory compulsion or perceived benefits to the service user) and information sharing on service user behaviour from other agencies, in particular the IDVA service.”

This would appear to include, in some cases, a rather traditional approach, e.g.,

“‘Counselling’ from a trained Domestic Violence Prevention Programme (DVPP) facilitator”

recalling that all accredited DVPP’s are essentially Duluth. However, the evaluation also notes, perhaps more encouragingly, that,

“Work on impulse control and emotional regulation stood out in interviews with service users.”

However, the direct work was far less significant than the indirect work in the pilot – and, one presumes, this would also be the case in more widespread application of Drive. Do note this crucial fact,

- 84% of the work with perpetrators was indirect.

Indirect work is that referred to as “disruption” above. My description of this “indirect work” as a system of surveillance is justified by the following quote from the evaluation,

“Some notable examples of indirect work oriented to disruption and risk management were:

- Information sharing to heighten risk awareness – while information sharing might be considered a ‘pathway to disruption’ rather than the disruption itself, it is a critical component in disruption activity.

- Providing the service user’s address to police or social services – case managers will often have done significantly more research on service users than other agencies have been able to. It can be as simple as providing an address to police or social services when it was not previously known, which can open an avenue for disruption work.

- MAPPA referrals* – in cases where the likelihood of behaviour change in the short to medium term was judged to be very low and the risk remained high, referrals to MAPPA were made.

- Referrals to social services…..referrals to social services can serve as a key disruption strategy by initiating a home visit.

- Breach without reliance on victim-survivor to report – for example, in one case, the service user was making repeated calls to the victim-survivor’s address in breach of his restraining order. The victim-survivor was too scared to make a complaint, in part due to complicity in the abuse from other family members. The case manager notified the housing provider and requested that they call the police if the service user attended the property. The housing provider agreed and did call the police.”

* MAPPA stands for Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements. It is the process through which various agencies such as the police, the Prison Service and Probation work together to protect the public by managing the risks posed by violent and sexual offenders living in the community.

There are three categories of MAPPA offenders. Category One comprises all registered sexual offenders. Category Two comprises violent offenders who have been sentenced to 12 months or more, or to detention in hospital, and who are now living in the community subject to Probation supervision. Category Three comprises other dangerous offenders who have committed an offence in the past and who are considered to pose a risk of serious harm to the public. My understanding is that MAPPA is applicable only to people who have been convicted, so referral of Drive “service uses” who have not been convicted to MAPPA would be illegal. The MAPPA system is overtly a surveillance system.

I have a concern that invoking MAPPA for domestic abusers is itself an abuse of the system, as MAPPA is intended to be used only when there is a danger to the wider public.

In summary, the Drive process consists mainly of a case manager who keeps a watching brief on the perpetrator and ensures that all relevant agencies are informed of any developments so that, together, the system as a whole puts a tight net around the “service user”. Clearly, this is not so much a service to the “perpetrator” as an extension of the existing processes of monitoring and external control. It is a system of surveillance.

The Structure of the Pilot

There are four distinct groups of people involved in the pilot of Drive, two groups of perpetrators (Drive pilot and control) and two corresponding groups of victims. Data from the victims were obtained via IDVA support to the victims. (IDVA = Independent Domestic Violence Advisor). The numbers in each group were,

- Perpetrators (“service uses”) within the Drive pilot, 506;

- The victims associated with the service users, of which 104 had IDVA support;

- A large number of perpetrators were initially identified as potential controls, but this eventually reduced to 353 who also had IDVA support for the associated victims.

The Evaluation’s Claims for DRIVE

Now let’s look at what the evaluation claims to be Drive’s achievements. The first Key Finding is stated as being,

“The number of Drive service users using each type of domestic violence and abuse (DVA) behaviour reduced substantially. For example, the use of high-risk…

- physical abuse reduced by 82%;

- sexual abuse reduced by 88%,

- harassment and stalking behaviours reduced by 75%;

- and jealous and controlling behaviours reduced by 73%.”

Well, that sounds pretty impressive, doesn’t it? The second of the Key Findings is,

“For both the Drive-associated victims-survivors group and the victims-survivors in the control group, IDVAs perceived a significant or moderate reduction in risk in over three quarters of cases over the period of the intervention. The overall trend was a reduction in risk for both groups, with a stronger reduction for Drive associated victims-survivors:

- IDVAs assessed risk as ‘permanently eliminated’ at the point of case closure in almost 3 times as many cases for victims-survivors in the Drive associated group (11%) compared to those in the control group (4%).

- Drive victim-survivors were more likely (82%) to experience a moderate or significant reduction in risk than their control counterparts (78%).”

Now some concern begins. If both the Drive group and the control group showed reductions, was the improvement attributable to Drive significant? It was not, as we shall see.

The third Key Finding is,

“MARAC data shows that Drive helped to reduce high-risk perpetration including by serial and repeat perpetrators, and this was sustained for a year after the case was closed: Drive service users appeared at MARAC less often (mean= 2.7 times) than perpetrators in the control group (mean= 3.3 times). This difference was statistically significant.”

The explicit mention that the difference due to Drive was statistically significant in this case only highlights the absence of this crucial claim in the previous Key Finding. But the MARAC data has other problems, as we will see.

My Critique (1): Assessed Changes in Victimisation

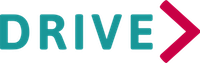

The victims themselves do not directly provide the data on victimisation and its changes over time. Rather these data are obtained by “Analysis of Insights data, completed by IDVAs”. The evaluation tells us that this, “showed that similar trends were observed for both Drive and control victim-survivor groups in the reduction of abuse experienced from intake to exit, and these changes were statistically significant”. Note that the statistical significance of the changes in assessed victimisation over time is not a measure of the effectiveness of the Drive process (though one may suspect the authors were hoping to create that impression). Only the difference between the Drive group and the control group provides a measure of the effectiveness of the Drive process – that’s what a control group is for. Within a minute or so of first looking at the evaluation report I spotted Figure 24, reproduced below, which is what leads to the unravelling of the edifice of misdirection presented as “evaluation”…

The immediately obvious feature of Figure 24 is that there seems to be little difference between the Drive group and the control group, either at “Intake” (before the Drive process occurs) or at “Exit” (after the Drive process, typically lasting about 10 months).

The crucial feature of Figure 24 is that it reveals that victimisation reduces to far lower levels than at intake for the control group with no Drive intervention. The report does not enlighten us as to why this might be. Possibly it is something to do with the IDVAs influence, but I need not speculate upon this.

The question which arises is: if one looks at the difference between the Drive group and the control group as regards the reduction in victimisation, are these differences statistically significant. Despite the Key Findings of the Executive Summary choosing not to tell us, the report itself does. On pages 70/71 regression analyses are described and the conclusion is stated clearly,

“Results indicated that the difference in changes of the four DVA behaviours from intake to exit were not statistically different between the Drive and control victim-survivor groups as indicated by p-values (see regression results in Appendix 4, Section 1).”

I invite you to look back at the wording of the second of the Key Findings, quoted above, which gives the opposite impression. That Key Finding is profoundly dishonest. If that were published in a peer reviewed journal, and its mendacious nature discovered, the journal would be obliged to withdraw the paper and the authors would be treated with some suspicion thereafter.

This is an example of a familiar phenomenon in advocacy research of this kind, which now infects all of social science. What is written in an Abstract or a Summary or a Conclusions section can be rather different from what one finds within the body of the text. It seems that the authors salve their consciences by “fessing up” in the text – which almost no one will read – but the desired spin is presented in the briefer material which people do read.

My Critique (2): Assessed Changes in Perpetrators’ Behaviour

How are changes in perpetrator behaviour quantified? This is revealed, rather hidden away in footnote 16,

“Case managers assess DVA behaviour from a variety of sources including service user, from victim-survivor (through IDVA support) and other information from multi-agency partners such as police, children’s social services, probation etc.”

In short, the case managers provide the measures of perpetrator behaviour. One may have a concern over the objectivity of this.

Recall the first Key Finding, above, and the apparently impressive reduction in perpetration behaviours, between 73% and 88%. Looking back at Figure 24, above, this no longer appears so impressive as, according to the IDVAs’ assessment of victimisation, there were statistically equivalent reductions without Drive intervention. Unfortunately, there appears to be no equivalent of the case managers’ assessments of perpetration behaviours applied to the control group. This is very unfortunate indeed because, given that the IDVA data of Figure 24 turned out to indicate no significant benefit of Drive, one is naturally inclined to expect the same would be true for the case managers’ assessments (necessarily so if the measures were truly objective and reasonably accurate, as they would be measuring the same thing).

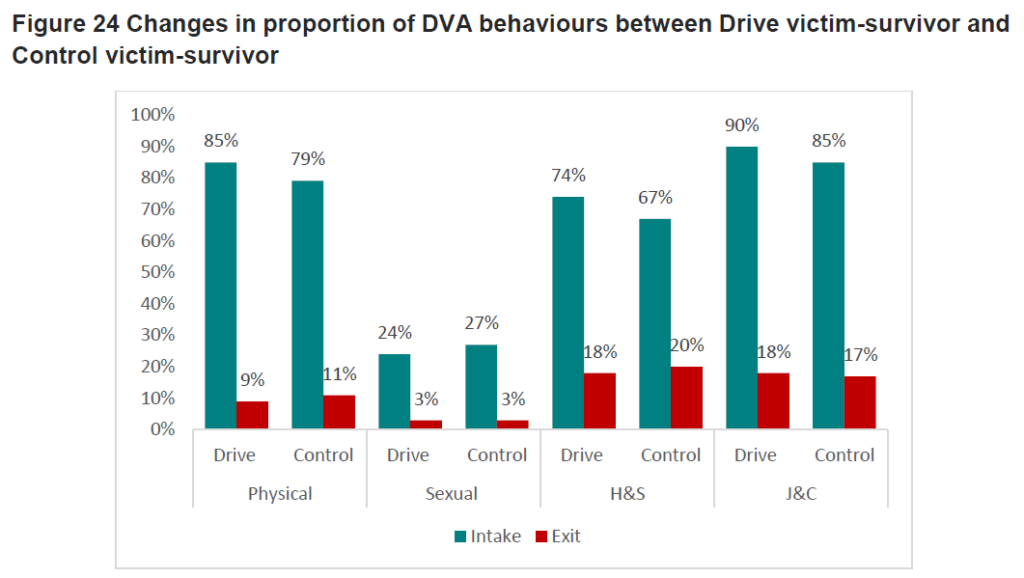

The only indication of the effectiveness of Drive intervention that is discernible from the case managers’ assessments of perpetrator behaviour changes relates to the “direct” element of Drive alone. Out of those perpetrators subject to “direct” work, 54% engaged with case managers, 31% did not engage and 15% were partially engaged. Figure 23, reproduced below, compares behaviour changes for these engaged, not engaged, or partially engaged, perpetrators. Following Figure 24 we are no longer impressed by the reductions per se, but are only interested in whether “engagement” results in greater reductions. There is no consistent indication that it does, though one must be mindful that all these perpetrators were potentially subject to the “indirect” work implicit within the Drive process.

Moreover, whether the couple were living together or not overturned any apparent benefit from “direct” support, quote “those service users who received one or more ‘direct support’ actions from the case managers were more likely to reduce high physical violence than those who did not receive direct support. This finding changed when adjusting for living situation, showing that direct support could increase physical violence. The other DVA behaviours showed no association with ‘direct support’ in the adjusted model.”

In summary, we can conclude nothing as regards the efficacy of Drive from the case managers’ assessments of perpetrator behaviour changes.

My Critique (3): Repeat MARAC Evidence

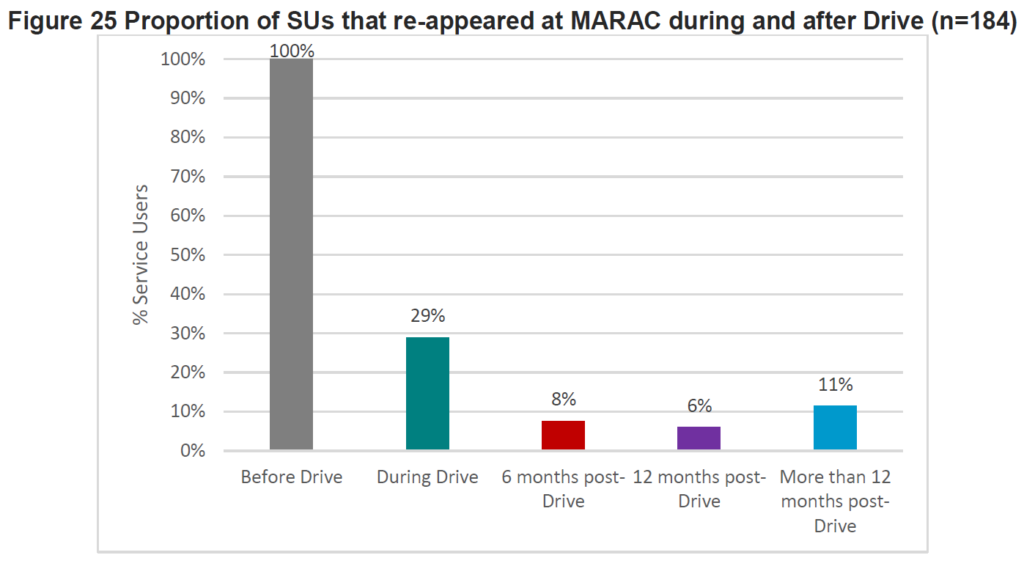

The evaluation puts considerable emphasis on the frequency of appearance of service users at MARACs during or subsequent to Drive intervention. However, some serious questions arise. Figure 25, reproduced below, purports to give the percentage of Drive service users who appeared at MARACs during or after Drive.

The most obvious, and most suspicious, absence from Figure 25 is the control data. There must be available data on control group re-appearances at MARACs over the same periods of time. Why are these data not shown? Without them we again cannot conclude anything about the effectiveness of Drive in reducing the need for repeat MARACs as regards the whole cohort of the pilot study.

Moreover, I have a serious doubt that the data plotted in Figure 25 is meaningful at all, even for the Drive group. The sub-group used consisted of the 184 service users from “Site 2”. After 6 months there were a total of 15 service users who re-appeared at MARAC, hence giving the 8% figure (i.e., 15/184) in Figure 25. Now consider this quote relating to the figure for 12 months,

“Data for 12 months after case closure was available for 64% of service users (n=117). The number of service users who appeared back in MARAC at 12 months post-intervention, was 12 service users (6%) showing an overall reduction in re-appearance by service users at MARAC during this period.”

To obtain the 6% figure, 12 has been expressed as a percentage of 184. But actually 12 repeat MARACs were found from a reduced number of cases of only 117, i.e., 10%. This is a minor issue, except for what it implies regarding the figure used for “beyond 12 months”. Quote,

“For 11% of service users (n=20) it was possible to calculate what their re-appearances were more than a year after case closure. Although this might not be representative of the service users as a whole for site 2, the number of service users who appeared back in MARAC after more than a year post-case-closure increased to 11% of service users.”

This seems to be saying that data on repeat MARACS was found only for 20 of the original 184 service users. But worse, it implies that all 20 appeared at repeat MARACs! The 11% figure is obtained as 20/184, but actually 100% of those for which there was information appeared at repeat MARACs! Figure 25 is therefore grossly misleading at best.

However, the third Key Finding refers to this, “control cases appeared slightly more frequently in MARAC (mean= 3.3 times) than those perpetrators who were allocated to Drive (mean=2.7 times). This difference was statistically significant (p<0.001).” The data on which those mean factors are based are not given, and it is unclear to me what they mean. My best guess is that they are averages only over those perpetrators who had repeat MARACs during the period in question, not over the whole Drive group even for “Site 2”.

Perhaps more simply, is it not reasonable to question the efficacy of a preventative process when service users need repeat MARACs during, or shortly after, the intervention, an average of 2.7 times?

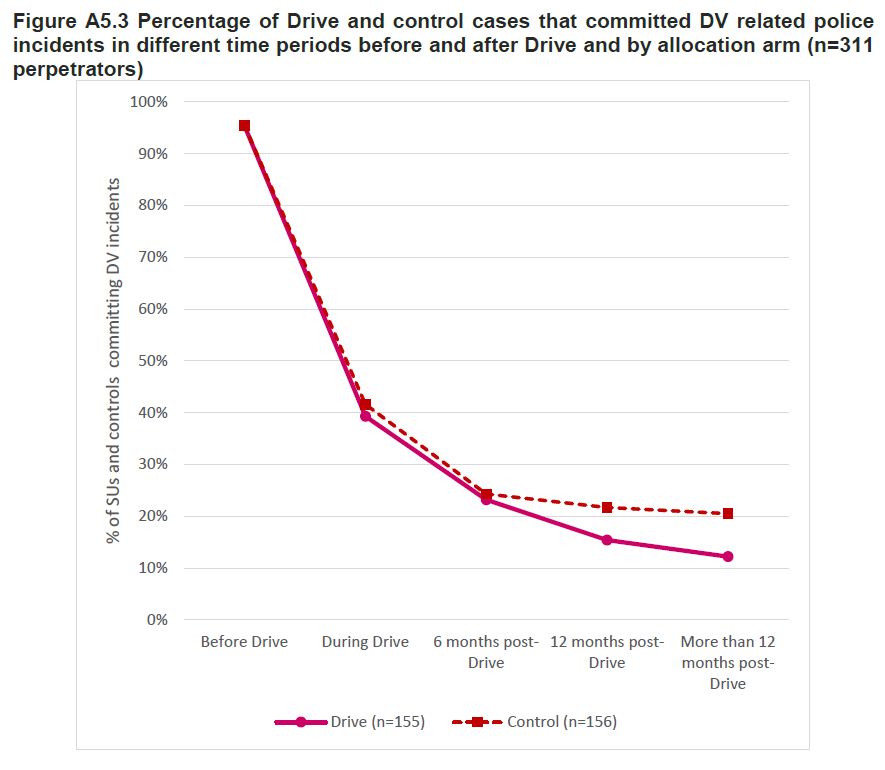

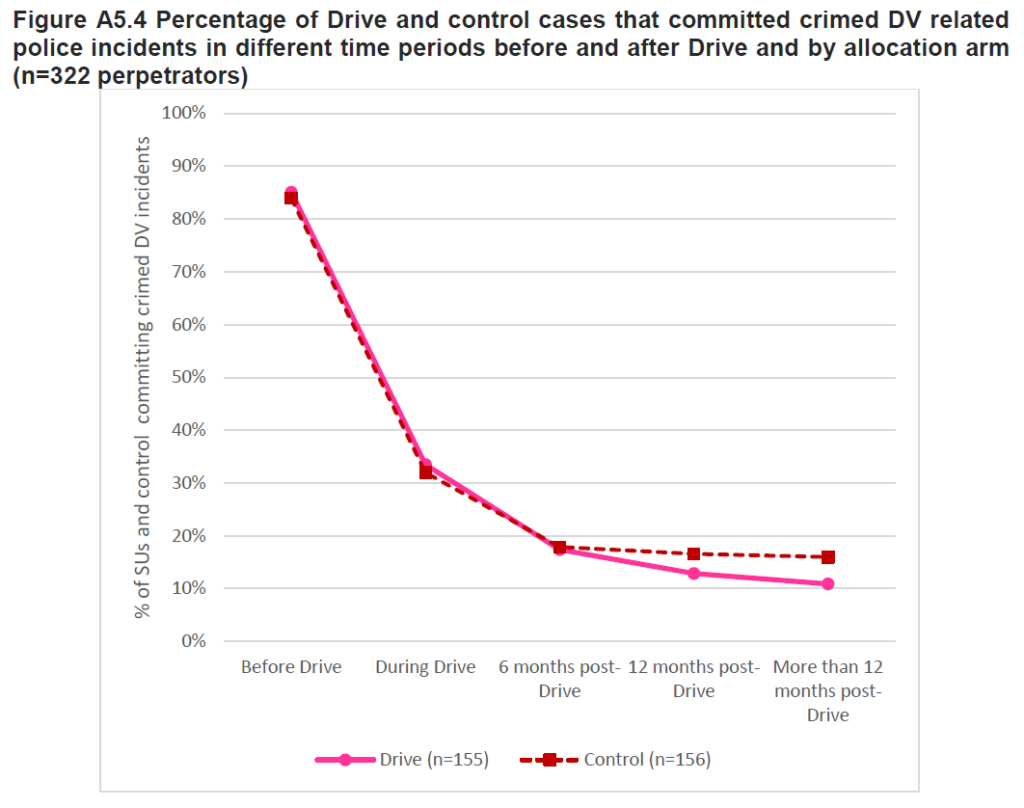

My Critique (4): Police Data on Repeat Offending

I reproduce below Figures A5.3 and A5.4. Figure A5.3 gives the percentage of the group committing DV related incidents against time from intake, comparing the Drive group with the control. Figure A5.4 is the same but restricted to incidents that were designated as crimes by the police (“crimed”). Impressed? It’s hard to be. If there is zero improvement by 6 months, it is hard not to interpret the apparent improvement thereafter as statistical fluctuation. The stand-out feature of the police data, like the data from the IDVAs (Figure 24) and case managers (Figure 23) is that, with or without Drive, the frequency of offending diminishes rapidly anyway. So why bother with Drive?

My Critique (5): Drive-DASH Changes

The DASH-Safelives Domestic Abuse “RIC” (Risk Indicator Checklist) provides a score, from 24 questions, the higher the score the greater the assessed risk. A score of 14 or more is usually taken as “high risk”, sufficient to motivate a MARAC. This is a reasonable tool for assessing a potential victim’s risk.

As part of the Drive pilot, a modification of that standard tool was introduced which I address briefly here only because it seems so preposterous. While the proper DASH tool is completed by victims (with guidance), the Drive-DASH was completed by the case manager. This is very weird since the case managers did not even work with the victims but only with the perpetrators (and only a small proportion of them!). Moreover, the number of questions on the Drive-DASH was reduced between Year 1 and Years 2 and 3, rendering any comparison meaningless. Finally, there were many “not applicable/not known” responses and the number of these varied across time. In summary, any variation in the Drive-DASH score over time is totally meaningless – but this did not stop Figure 20 being included in the report.

Cost of Drive

The pilot cost £2,400 per perpetrator (hence £1.2M). This will reduce to about £2,000 per perpetrator in subsequent applications. The estimated cost per annum of delivering Drive in all PCC and police force areas across England and Wales is stated as £9M, although I don’t know how this relates to the approximately 76,000 MARACs cases which would suggest £152M.

Conclusions

(1) The Drive process is less a conventional DVPP and more a surveillance system.

(2) Perpetrator abusive behaviours reduced markedly over approximately one year for both the Drive group and the control group, for reasons unknown.

(3) Any changes in perpetrator behaviours, as assessed by IDVAs and attributable to Drive are not statistically significant.

(4) Direct support by Drive case managers had no beneficial effect on perpetrator behaviours when account was taken of living arrangements (together cf apart).

(5) It is disgraceful that the lack of statistically significant benefit in respect of (3) and (4) is hidden in the Executive Summary, the impression being given of substantial benefit.

(6) Police recorded incidents of abusive behaviours reduced markedly over approximately one year for both the Drive group and the control group. There was no difference between them for six months. Thereafter any difference is of unknown statistical significance.

(7) The “evaluation” is not a neutral academic evaluation but a marketing advertisement for Drive.