In my book, The Empathy Gap, section 19.6, I discuss false allegations of rape and the difficulty of obtaining a secure estimate of the rate of false allegations due to the extremely wide spread of reported data. However, I also show in that section, using only data from National Statistics, that 77% of allegations of rape made to the police appear to be false.

This brief note addresses a different question: the rate of false allegations of domestic abuse made in the context of Private Law Children Act cases in the Family Courts in England and Wales. My conclusion is grossly in conflict with the claims made in the June 2020 Family Justice Review that only a very small proportion of such allegations are false. I show here that this claim by the Family Justice Review is unsupported by the review itself, despite appearances to the contrary.

Indeed there appears to be no evidence at all to support the contention that the rate of false allegations in the family courts is small. In contrast two simple and independent arguments presented below, and based on National Statistics alone, indicate that most of such allegations are false.

1. The Prevalence of Allegations in the Family Courts

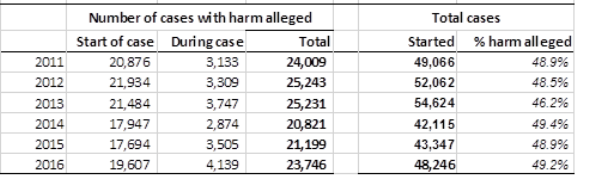

The best data for the percentage of private family law cases involving allegations of domestic abuse was provided by the Ministry of Justice research team as a private communication to FNF-BPM Cymru together with HMCTS (HM Courts & Tribunals Service), and is shown in Table 1 below.

The best estimate is therefore that 49.2% of private family law cases involve allegations of domestic abuse. Independent support for a figure close to 50% comes from academic studies by Hunt and MacLeod (2008) and Harding and Newnham (2015) both of which involved allegations of domestic abuse in very close to 50% of their samples of cases. In June this year (2020), the literature review conducted by Adrienne Barnett for the MOJ’s Family Justice Review compiled nine sources which all showed allegation rates in child arranagement cases of about 50% or greater (see Table 4.1 of this report).

2. Prevalence of Partner Abuse and Domestic Abuse in the General Public

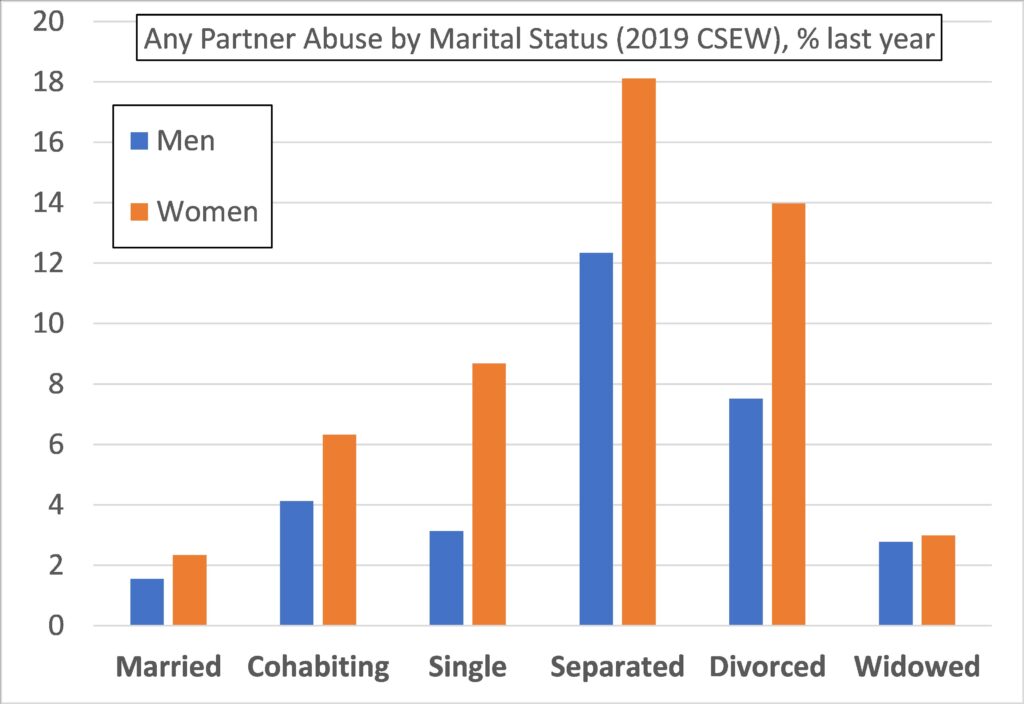

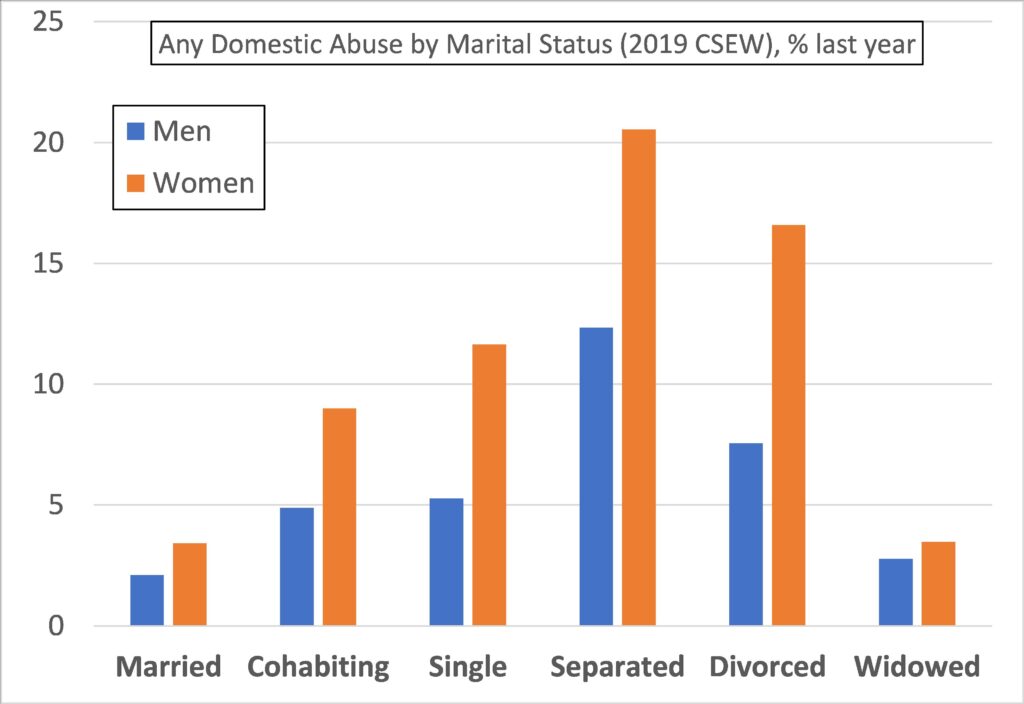

The annual Crime Surveys for England & Wales (CSEW) are generally regarded as the best indicators of the true volume of crimes, including intimate partner abuse. Figures 1 and 2 below have been plotted from the data in Table 6a of the 2019 CSEW release.

Figure 1 shows all partner abuse against people aged 16 to 74, including sexual abuse, by sex of victim, broken down by marital status: married, cohabiting, single, separated, divorced or widowed. (Recall that partner abuse does not require the partners to be living together, or ever to have lived together). Each bar of the histogram indicates the percentage of respondents with that marital status who reported partner abuse in the survey.

Figure 2 is the equivalent for all domestic abuse of people aged 16 to 74, and hence includes abuse between parents and offspring, and between siblings – or any other relationship within the domestic setting.

It is clear that partner abuse, and domestic abuse generally, is far more prevalent amongst the separated or divorced, and least common amongst married couples (a fact about which the popular media is strangely quiet).

3. Implications for the Rate of False Allegations

As 50% of private law cases involve allegations of abuse, but Figures 1 and 2 indicate that even for the case of separated couples the true underlying rate of abuse does not exceed 20% according to the CSEW (our best guide) the implication is that 60% of allegations of abuse in the family courts are false.

A potential problem with that estimate needs discussion, namely that the abuse data of Figures 1 and 2 relate to abuse suffered “in the last year”. There is therefore a potential for larger prevalence figures to apply if earlier years were also taken into account. In this respect note that we are interested in counting victims, not counting incidents. Hence, the data will not be affected by earlier abuse suffered by a victim who also suffered abuse in the last year (since that victim is already counted). Any enhanced prevalence can only relate to individuals who suffered no abuse in the last year, but did suffer abuse in earlier years. However, there are likely to be few such cases for separated couples, for the following reason.

The dominant feature of Figures 1 and 2 is the strong association between the prevalence of abuse and being separated or divorced. The prevalence of abuse is highest in the “separated” category, indicating that abuse tends to peak soon before, or soon after, separation. Consequently, cases of separated couples where there has been no abuse in the last year, but there was abuse earlier, are anomalous in relation to the trend suggesting there will be very few such cases.

In passing I note that the sampling used by ONS/CSEW reproduces reasonably well the proportions of the general population within the various marital status categories (see here).

4. Estimate from Police Recorded Domestic Abuse Data

In England & Wales, Table 13 of the 2019 CSEW indicates that the number of offences recorded by the police and flagged as “domestic abuse related” was 746,219 in the year ending 31 March 2019. However, Tables D7 to D9 of the corresponding demographics tables indicate that most of these incidents were repeat incidents involving the same victim. The average number of incidents per victim may be found from the data in these Tables to be at least 3. Hence the number of victims of domestic abuse recorded by police in that year was about 250,000.

In round numbers about 55,000 private law Children Act cases go through the family courts in England & Wales per year (having continued to increase beyond the dates covered by Table 1), hence involving about 110,000 parents. This is 0.23% of the adult population of England & Wales (which is 48 million aged 16 and over). Hence, if these 110,000 parents were a random cross-section of the public we could expect 0.23% x 250,000 = 575 parents in private family law to have reported domestic abuse to the police.

However, these 110,000 parents are not a random cross-section of the public. We have seen from Figures 1 and 2 that separated partners experience far higher levels of abuse. For partner abuse, the largest figures are for separated women, being 18%, or 15% of both sexes combined. These figures compare with the population average partner victimisation of women of 5.6%, or 4.2% for both sexes combined (Table 1a of the CSEW). Hence, separated people experience 3.6 times the prevalence of abuse compared to the average. Hence, in round numbers we could expect that, say, 3.6 x 575 ≈ 2,100 parents in private family law would have reported domestic abuse to the police. This compares with about 27,500 allegations of victimhood being made within the family courts (i.e., 50% of 55,000).

The huge gap between the expected 2,100 people reporting domestic abuse to the police, and the 27,500 allegations of victimhood made in court is considerably reduced when account is taken of the known under-reporting of domestic abuse. Table 1 of Ref.6 indicates that only 17.3% of people reported the offence to police (or 20.8% averaged over the last four years). Hence the 2,100 reports to police would correspond to up to about 2,100 / 0.173 ≈ 12,000 actual offences. [It is worth noting that for those that did not report abuse to the police, the most common reason was that the abuse was too trivial or not worth reporting, 45.5%].

Finally, then, a generous estimate is that 12,000 of the 55,000 cases in private law per year might be expected to involve domestic abuse. This compares with about 27,500 allegations being made, so we conclude that 56% of allegations of domestic abuse made in private family law are false. This is indeed very close to the estimate made without using police data in section 3 (i.e., 60%).

Moreover, based on the CSEW survey evidence, 45.5% of the (genuine) 12,000 victims would have regarded the offence in question to be “too trivial to report” – before they were involved with the family court, that is. This suggests that 76% of allegations of domestic abuse made in the family courts are either false or too trivial to have a bearing on court proceedings.

5. The MOJ’s Family Justice Review

The Family Justice Review Panel, and the associated report authors, are knonw to be partisan with a record of advocacy on behalf of mothers. There were no balancing voices speaking for fathers at all. The Family Justice Reports were published in June this year (2020). The main report makes this statement,

“The literature suggests that there is a perception amongst some professionals that mothers in child arrangements cases make false allegations of domestic abuse as part of a ‘game playing’ exercise to delay or frustrate contact. However, research suggests that the proportion of ‘false’ allegations of domestic abuse is very small.”

The Main Report references section 7.2 of the companion Literature Review by Adrienne Barnett in support of this contention. (I have reviewed some other of Dr Barnett’s work previously, here). Only one paragraph of that section addresses the issue of false allegations. It is this,

“Hunter and Barnett (2013) noted that whenever objective efforts are made at quantifying ‘false allegations’ of domestic abuse, the proportion of unfounded allegations turns out to be very small. Allen and Brinig (2011) found not only that ‘false’ allegations in divorce proceedings (including in applications for protective injunctions) constituted only a very small proportion of domestic violence claims, but that the ratio of men to women making false claims was 4:1. Some professionals interviewed by Harwood (2019) commented that the prevalence of false allegations is hard to gauge because they are so rarely tested.“

The last sentence is true. Findings-of-Fact are held very seldom to examine domestic abuse allegations in the family courts (the Literature Review by Adrienne Barnett indicates typically fewer than 10%, often far fewer). Even when fact finding hearings are held, they are rarely conclusive.

The above quote appears to include two sources of support for the contention that false allegations constitute “only a very small proportion of domestic violence claims“, namely Hunter and Barnett (2013) and Allen and Brinig (2011). Actually there is only one, the latter paper, because – when one takes the trouble the read Hunter and Barnett (2013) – one finds that all it contains on the matter is this,

“The spectre of false allegations is a recurrent trope in all discussions of domestic violence, but whenever objective efforts are made at quantification, the proportion of unfounded allegations turns out to be very small.“

…and then cites the same Allen and Brinig (2011) paper in support of this claim. It would apears that after many years devoted to these studies, these leading experts in the field have only that one source to support their contention that false allegations constitute “only a very small proportion of domestic violence claims“.

I note in passing that Rosemary Hunter was one of the authors of the Final Report of the Family Justice Review and Adrienne Barnett is the author of the associated Literature Review. Both these authors have been partisan advocates on these matters for many years. They are guilty here of trying to big-up the support for their contention that false allegations are rare by circular reference – to hide the extreme sparsity of such support.

It turns out that the support for their contention that false allegations are rare is non-existent because Allen and Brinig (Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Volume 8, Issue 2, 304–324, June 2011) does not provide it either.

Let us note immediately that this reference uses data from the State of Oregon in 1997. In a different jurisdiction, in a different Nation State, and 23 years old, there is a rather obvious question-mark over the relevance of this work to England & Wales in 2020. That this is the best ‘evidence’ that Hunter and Barnett can dredge up is telling in itself.

But the key issue is the definition of “false allegation” used by Allen and Brinig. Their definition is given in this quote.

“the divorce records contain information on whether accusations of domestic violence (abuse) were made and whether or not the court issued protective orders based on these accusations. We call cases where an abuse claim was made but no order issued a ‘false claim’. “

But this is an utterly preposterous misuse of language. Protection orders are issued based on the complainants claim – essentially as a precaution pending later investigations (which generally never come). This presupposes that all cases where a Protection Order was issued were valid allegations. But this brings us right back to “believe-the-complainant”. It is circular logic which assumes what it purports to prove.

This ridiculous definition of “false allegation” explains the extraordinary claim, based on Allen and Brinig, that “the ratio of men to women making false claims was 4:1“. If that claim did not make the MOJ question the veracity of the source, one wonders if they read their own report at all. Now we see that all that statement really means is that Protection Orders are refused four times more often when the complainant is male. Quelle surprise!

We can be sure that if any real evidence existed to support the claim that the proportion of false domestic abuse allegations in the family courts is small, then Hunter and Barnett, and the rest of those involved in the Family Justice Review, would certainly have found and reported it. We can conclude there is no such evidence.

6. Conclusions

Two independent methods, based on national statistics alone, imply that about 56% to 60% of allegations of domestic abuse made in private law cases in the family courts are false.

Moreover, 76% of such allegations are either false or too trivial to have a bearing upon the court proceedings.

Claims made in the Family Justice Review that “the proportion of ‘false’ allegations of domestic abuse is very small” are unsupported, the apparent support provided in the Literature Review being fatally flawed, if not actually fraudulent.

7. Recommendations

The magnitude of the impact of the above findings on the Family Justice Review, and the fact that this high rate of false allegations has been ignored, invalidates the Family Justice Review, which should therefore be withdrawn.

The simple arguments presented here cannot be unknown to the authors of the Family Justice Review reports, given their many years experience in these matters. This implies that the gross misrepresentation of false allegations within the Family Justice Review reports must have been done deliberately to mislead the MOJ on this key issue.

Authors who set out deliberately to mislead should not be employed in future reviews.