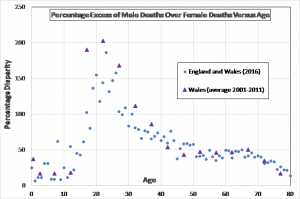

Percentage Excess of Male over Female Deaths Versus Age (England and Wales) – click to enlarge

The focus of this post is men’s accessing healthcare in the UK. Before turning to that I give a brief summary of men’s health disadvantage in terms of early or premature death. The implicit question is whether men’s lesser accessing of healthcare services is to blame for their higher death rate – or whether this is just another case of “it’s men’s own fault”. Scroll down to the second part below the two Tables if you wish.

When it comes to disadvantage, being dead takes some beating. And when it comes to dying, that’s one area where male dominance remains unchallenged.

Gender Gap in Longevity

More males die young – see the graph which heads this post.

All data below refers to England and Wales

One man in five dies before he reaches 60. Two in five by 70.

Defining premature death as death before age 75, there is a premature death gender gap of 43%. A male has a 43% greater chance of dying before reaching 75 than a female.

Defining early death as death before age 45, there is an early death gender gap of 75%. A male has a 75% greater chance of dying before reaching 45 than a female.

Premature Death (<75)

The top causes of premature death (before age 75) are cancers, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and digestive system diseases, in that order for both sexes, accounting in total for 80% of premature deaths of men, and 82% of premature deaths of women.

In terms of the gender gap in premature death, the top causes in order are cardiovascular diseases, cancers, digestive system diseases and suicide (see Table 1 for the complete list). If drugs and alcohol were combined they would come in at 3rd position. If drugs, alcohol and suicide were combined, they would come in at 2nd position.

More than twice as many men die prematurely from cardiovascular diseases as women.

The number of premature male deaths from cancers exceeds the number of premature female deaths from cancers by 16%. All types of cancer result in more premature deaths of men than of women, excluding only the female-specific cancers of breast, cervix, ovary and uterus (noting that some men do die of breast cancer – in fact, more men die of breast cancer than of testicular cancer, though the numbers in both cases are small).

By far the largest cancer killer, for both sexes, is lung cancer and there is a strong socioeconomic dependence in the incidence of lung cancer. The most disadvantaged quintile is about 2.6 times more likely to die from lung cancer than the least disadvantaged quintile. This is explicable in terms of the prevalence of smoking by demographic.

Prostate cancer has now overtaken breast cancer as a cause of mortality. However, a greater proportion of breast cancer deaths are premature (before 75), so prostate cancer is responsible for about half as many premature deaths as breast cancer. Nevertheless, prostate cancer is the 4th most important premature cancer killer in men.

Claims in some quarters that inter-personal violence is one of the top killers is simply false. Of the 21 causes of premature death listed in Table 1, homicide is nineteenth in terms of numbers of premature male deaths caused, and twentieth for women.

Early Death (<45)

“Early” death may be defined as death before age 45. Table 2 lists 17 causes of death and gives for each cause the gender gap in the numbers of male and female deaths before age 45 (and the ratio of male to female deaths). There is an excess of early male deaths over early female deaths for all causes other than cancers.

In contrast to premature deaths, the two most significant causes of excess early male deaths are suicide and drugs, knocking cardiovascular diseases into third place. Table 2 confirms the frequently made claim that suicide is the biggest killer of men under 45.

Table 2 again confirms that the significance of inter-personal violence as a killer is exaggerated in popular discourse. Of the 17 causes of early death listed, homicide lies in 14th place in terms of the number of early deaths of men, and in 15th place for women.

Table 1: Gender Disparity in Premature Death (<75) in England and Wales (2016), listed in order of excess male deaths

| Cause of Death | Excess Male Deaths# |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 13,087 (2.10) |

| Cancers | 5,032 (1.16) |

| Digestive system diseases | 2,452 (1.55) |

| Suicide | 2,421 (3.24) |

| Respiratory diseases | 2,188 (1.28) |

| Alcohol | 2,184 (1.98) |

| Drugs | 1,400 (2.19) |

| Transport accidents | 872 (3.81) |

| Falls, Drowning, Fire | 498 (1.93) |

| Endocrine diseases | 441 (1.36) |

| Diseases of the Nervous System | 411 (1.13) |

| Undetermined, including Sudden Infant Death | 380 (1.96) |

| TB, HIV, Sepsis, Hepatitis, Meningitis | 225 (1.26) |

| Homicide | 215 (2.38) |

| Poisoning by noxious substances other than drugs or alcohol | 175 (2.24) |

| Congenital & Chromosomal | 112 (1.22) |

| Mental/behaviour disorders | 112 (1.09) |

| Diseases of the blood or blood forming organs | 87 (1.47) |

| Diseases of the skin, musculoskeletal system, or genitourinary system | -161 (0.89) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | -119 (0.79) |

| Diabetes | 354 (1.57) |

| ALL CAUSES* | 32,014 (1.43) |

*Exceeds the sum of table entries since not all causes are listed; #Figure in parentheses is the ratio of male to female deaths

Table 2: Gender Disparity in Early Death (<45) in England and Wales (2016), listed in order of excess male deaths

| Cause of Death | Excess of Male Deaths# |

| Suicide | 1,298 (3.63) |

| Drugs | 924 (3.46) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 740 (2.17) |

| Transport accidents | 546 (4.33) |

| Alcohol | 317 (1.86) |

| Digestive system diseases | 292 (1.60) |

| Falls, Drowning, Fire | 187 (3.92) |

| Undetermined, including Sudden Infant Death | 146 (1.95) |

| Homicide | 146 (2.55) |

| Diseases of the Nervous System | 121 (1.37) |

| Poisoning by noxious substances other than drugs or alcohol | 99 (3.41) |

| Mental / behaviour disorders | 79 (2.11) |

| Endocrine diseases | 63 (1.27) |

| Respiratory diseases | 60 (1.16) |

| TB, HIV, Sepsis, Hepatitis, Meningitis | 39 (1.28) |

| Congenital & Chromosomal | 23 (1.10) |

| Cancers | -349 (0.81) |

| ALL CAUSES | 4,731 (1.76) |

#Figure in parentheses is the ratio of male to female deaths

Men Accessing Healthcare

One of the explanations put forward to explain men’s poorer longevity is that men “just don’t look after themselves”. Men, it is said, do not visit their GP or other health services when they should; they delay consulting a doctor when they have a medical problem, thereby disadvantaging themselves. Is this true? Or is it an instance of blaming men for their own disadvantage? Are poor health outcomes for men a product of a macho male gender script in which help-seeking is seen as weakness? Or is it a result of disadvantage imposed on men by society?

We have already seen, above, that men and boys are disadvantaged in terms of the ultimate health objective: staying alive. They are specifically disadvantaged in some ways associated with health provision for cancer prevention or detection. Within the NHS, women have screening programmes for breast and cervical cancers, and a national HPV vaccination programme. Men have no screening programme for male-specific cancers and are excluded from the HPV vaccination programme on grounds of cost, despite suffering similar HPV related mortality. Men are invited to no NHS screening programme until they are 60 years old.

There is also relatively poor provision for protecting men against prostate cancer. Though improvements are being made in prostate cancer diagnosis, there is a way to go yet due to the lack of an adequate primary diagnostic tool. To lay the blame for that on lack of suitable technology begs the question: is this the result of inadequate research funding?

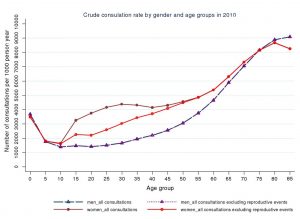

It is certainly the case that men in the UK visit their GP less often than women (Figure 1). But this does not necessarily imply that men are gratuitously disadvantaging themselves. Women visit their doctor in association with contraception, pregnancy, neonatal and postnatal issues, as well as in the context of screening programmes. None of these apply to men, or apply to a much lesser extent, so less frequent visits by men to their GP may be expected. In addition, it is known that people who work full time find it more difficult to attend GP appointments. This will affect more men than women, since more men work full time. So, are the less frequent visits by men to their GP a disadvantage imposed on them by their working patterns, rather than the fault of their self-destructive ‘hegemonic masculinity’?

Here I review some of the academic publications to shed light on the reasons for men accessing health services less often than women.

In 2008, Wilkins et al of the Men’s Health Forum and the University of Bristol were commissioned by the Department of Health to examine the role of gender in the access to health services in the UK. We have seen that the gender gap in premature death rate is dominated by cardiovascular diseases and cancers. This is what Wilkins et al had to say about accessing health services by men and women in the context of cardiovascular problems,

“There are a number of studies which look at the gap between the onset of symptoms related to heart attack/acute myocardial infarction (MI) and the decision to seek treatment. However, the evidence is not clear cut in terms of whether women or men are more likely to delay. In addition, although delays in help-seeking have important clinical implications – increasing the risk of mortality or subsequent morbidity – research does not tell us whether differences in delay between women and men are long enough to have clinical implications.

One review of over 100 studies of treatment-seeking delay in patients with heart attack and stroke reported that women had longer delays before seeking help when experiencing symptoms of heart attack, but there were no differences between women and men when experiencing symptoms of stroke. A 2004 meta-analysis of delays in treatment-seeking reported that larger-scale studies with greater statistical reliability were most likely to report longer delays in seeking treatment for women than men. In addition, one study suggested that, while men and women were equally likely to delay, the time elapsed before seeking treatment was longer for women than men, increasing their mortality risk.”

Similarly, in the context of cancers, the relevant extracts from Wilkins et al are as follows – firstly on patient delays in seeking health care advice,

“For 10 different groups of cancers combined, 13 studies showed greater delay in men (10 of the studies were rated as strong methodologically, 2 moderate and 1 insufficient), 11 studies showed greater delay in women (8 strong and 3 moderate), and 23 studies found that gender had no impact (11 strong and 12 moderate). There was only one cancer where research was decisive, but this was because there was only one study for that cancer, otherwise gender had no impact or the effect of gender was inconclusive.”

And on practitioner delay,

“The review by Macdonald et al (2004) of research on delay uses the term ‘practitioner delay’ for the period between first consultation for symptoms and an appropriate referral. Overall, for the 10 different groups of cancers, four studies show greater delay when the patient was male (two strong methodologically and two moderate), six studies show greater delay for female patients (six strong), and four studies found that the gender of the patient had no impact (four strong). As with patient delay, there are conclusive results for individual cancers only when there has been a single study (on skin cancer, in which women had greater delay).”

In summary, Wilkins et al provide no support at all for the idea that men’s delay in accessing health services is responsible for their adverse outcomes in the two key areas of cardiovascular diseases and cancers.

In Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data Yingying Wang et al analysed GP consultation data from just under two million men and two million women from 2010. The crude consultation rate was 32% lower in men than women. Accounting for reproductive-related consultations substantially diminished but did not eradicate the gender gap (Figure 1). However, consultation rates in men and women who had comparable underlying morbidities (as assessed by receipt of medication) were similar; men in receipt of antidepressant medication were only 8% less likely to consult than women in receipt of antidepressant medication, and men in receipt of medication to treat cardiovascular disease were just 5% less likely to consult than women receiving similar medication. These small gender differences diminished further, particularly for depression, after also taking account of reproductive consultations.

Wang et al were unable to control for the effect of full time working, due to limitations in the recorded data. However, as can be seen from Figure 1, the sex difference in consulting rates is confined to the working years and disappears below 16 and rapidly disappears above 60. It seems likely that the effect of full-time working might be to eradicate entirely any residual sex difference. Support for this contention is obtained from other studies, discussed below.

A by-product of the analysis of Wang et al is the significance of socioeconomic status. The gender gap in consultation rate becomes successively greater as one moves down the deprivation quintiles. This is in line with the general trend that socioeconomic disadvantage affects men even more than women. Women in the most deprived quintile consult their GP approximately 10% more often than women in the least deprived quintile. In contrast, men in the most deprived quintile consult their GP about 4% less often than men in the least deprived quintile.

Figure 1: GP consultation rate per 1000 person-year by gender and age (5 years age bands) in 2010. From Yingying Wang et al. This graph does not include the effects of full time working nor the dramatically reduced gender gap for diagnosed morbidities (see text). Click to enlarge.

Ian Banks and Peter Baker, 2013, recognise the significance of full time working on men’s accessing health care services, and the exacerbation of this problem for men in relative deprivation. They note, “there are some specific groups of men that are likely to face additional barriers to accessing primary care. Low-income men in employment tend to have less flexible working hours and may lose pay if they take time off to attend an appointment….We now know that men will use primary care services that meet their needs. By providing a male-specific service that is also open in the evenings, the Camelon men’s health centre in Scotland succeeded in attracting significant numbers of men, particularly from its target group: men in their 40s, living in deprived communities.”

A report by the European Commission, Access to Healthcare and Long-Term Care: Equal for Men and Women? observes, “An additional cultural barrier that is worth mentioning mainly affects men and relates to the flexibility of services. An explanation given in the UK for men’s lower use of primary care services is that the opening hours are incompatible with the long working hours that characterise the UK labour market. Men are unable or uninclined to access primary care services because they are more likely than women to work full-time and to work more than 45 hours per week”.

Similarly, Alan White and Karl Witty, in their discussion of men’s under use of health services, noted that, (i) 80% more men than women in the UK work full time, (ii) three times as many women work part-time, (iii) 50% more women who work full time have flexible working arrangements, and, (iv) three times as many men as women work more than 45 hours per week. They conclude that, for men “attending for health checks during the working day is at best problematic, at worst impossible”. They go on to observe that the majority of community health promotion activities, such as weight loss groups, also take place during the working day.

The relevance of working patterns in men’s access to health services has also been raised by the National Pharmacy Association: “Men are twice as likely as women to have a full-time job and are more than three times more likely to work over 45 hours per week, making getting to a surgery or pharmacy more difficult” (89).

There are studies which, at least superficially, appear to blame men’s underutilization of healthcare services on negative masculine behavior traits. For example, in a review of the literature, Galdas et al conclude that, “the growing body of gender-specific studies highlights a trend of delayed help seeking when they (men) become ill. A prominent theme among white middle-class men implicates ‘traditional masculine behaviour’ as an explanation for delays in seeking help among men who experience illness.” But a curious aspect of this conclusion is that it is based on a dismissal of gender-comparative studies. In respect of gender-comparative studies the paper includes this summary,

“The review of key gender-comparative help seeking studies does not fully support the hypothesis that men are less likely than women to seek help when they experience ill health. Although many studies note the relative under use of health services and symptom reporting by men in comparison with women, conversely, many also find an increase in help seeking in men compared with women, or indeed, no significant difference in help-seeking behaviour between genders. The evidence suggests that occupational and socioeconomic status, among others, as more important variables than gender alone.”

Galdas et al leave one in the peculiar position of being asked to believe that men’s and women’s delay in seeking healthcare services are comparable, yet, at the same time, men’s delay is to be blamed upon ‘traditional masculine behaviour’. It rather begs the question: what causes women’s similar delay, then? One cannot help but be suspicious that the ‘gender-specific’ studies Galdas et al cite may have suffered from an over-willingness to make individual male behavior culpable for a socially imposed disadvantage, namely working patterns.

A similar conflict between ostensible conclusions and research content is to be found in the 2016 American study by Leone et al. The Abstract states that “Results suggest gender norms and masculine ideals may play a primary role in how men access preventative health care.”. But what we actually find within the paper is,

“Using hegemonic masculinity theory we explored whether predictors of men not accessing health care would be due to a threat to perceived masculinity (macho/machismo), stigma, reactivity, and weakness/vulnerability. However, stigma and weakness/vulnerability did not play a role in the prediction model. This was somewhat of a surprise being that male gender norms and masculinity are closely related such that endorsement of male gender role norms often prompts some men to adopt a hypermasculine (i.e., hegemonic masculinity) ideal. We found less rigid gender role norms in our participants.”

And,

“We also assessed our conceptual model as to whether the TNC (theory of normative contentment) would align to men not accessing health care. Specifically, we were interested in fatalism, denial, low awareness of risks, and low knowledge; this was somewhat consistent. Fatalism and lack of knowledge did not achieve statistical significance in our model.”

Leone et al do not discuss the role of working patterns in men’s health care access. A specific example where the role of work has been definitively established is Identifying Work as a Barrier to Men’s Access to Chronic Illness (Arthritis) Self-Management Programs by Lisa Gibbs. She concluded, “A qualitative study was conducted involving in-depth interviews with 17 men with arthritis. This paper discusses the role of work as one of the factors affecting men’s access to arthritis self-management services. Work was found to be a significant conceptual, structural, and social barrier due to: its role in relation to men’s concepts of health and fitness; practical difficulties in accessing services during business hours; and sociocultural influences resulting in prioritising of work commitments over health concerns. The structural, conceptual, and sociocultural work influences were more of a constraint for men in the middle stages of life when work and family obligations were greatest.”

In summary, the literature suggests that there is a smaller gender gap in accessing healthcare than is popularly believed, especially when the apparent gap is adjusted to allow for women’s greater access for contraceptive, pregnancy, childcare and national screening purposes. The latter is a disadvantage imposed on men, not an aspect of male behavior. The residual gender gap in access to primary healthcare, as displayed by Figure 1, is probably due in the main to men’s working patterns, and the resulting difficulties of access to healthcare and community health programmes during the working day.

There is a willingness to attribute men’s indisputable health disadvantages to men’s lesser use of healthcare services, and to attribute this to men’s negative masculine characteristics. However, this hypothesis crumbles upon inspection. Not only is men’s reduced access to healthcare not as marked as is often supposed, but the part of this reduced access which is not explained by valid sex differences in need may be explicable by working patterns. Whilst it might be argued that men’s working patterns are an individual choice, it would be disingenuous not to concede a societal – and practical – obligation which acts in this respect.

Finally, there are clear instances of poorer service provision for men, specifically in respect of less use of national screening programmes and the withholding of the HPV vaccination programme from boys. There are signs here that male health disadvantage is more due to society-wide acceptance of such disadvantage than it is to destructive masculine traits. Adopting a stance that traditional male gender norms are responsible (“it’s men’s own fault”) may be a subconscious means of denying the implied empathy gap.

What has not been explored here are the broader psychosocial factors which are obviously relevant in respect of deaths due to alcohol or drug abuse, or accidents or suicide. Nor have biological differences been addressed as causes of the excess of male deaths, though these are probably important in view of the impact of testosterone as an immunosuppressant and, from an evolutionary perspective, the essentially ‘disposable’ role of males of all species – the male genetic filter hypothesis.