The United Nations has just published a major study on children in custody worldwide. My thanks to the ever-energetic Douglas for alerting me to this UN study. The main report, by Manfred Nowak, is 758 page long. It identifies 7 million children in various types of custody, including police cells, prison, and detention centres. 94% of them are boys.

The panel which led the study consisted of 170 non-governmental organizations working directly or indirectly on children’s deprivation of liberty. Information was collected from every region of the world: 41 inputs from Europe; 27 from Africa; 20 from Asia, 19 from North and South America; and 11 from Oceania.

The treatment meted out to many of these children is extremely distressing, and I do not intend to go into those details here. One may hope – and expect – that children in custody in the UK do not experience such brutality. However, in terms of the gender ratio of children in custody, the worldwide data and UK data are similar – except that it is even more extreme in the UK, with 97% – 98% of children in custody here being boys.

The UN is hardly noted for being a man-friendly organisation. It drives a host of feminist agendas. That only makes what follows even more noteworthy.

I quote firstly the UN Secretary-General’s own words, from his relatively snappy 23 page report, “Global study on children deprived of liberty, Note by the Secretary-General, 11 July 2019”.

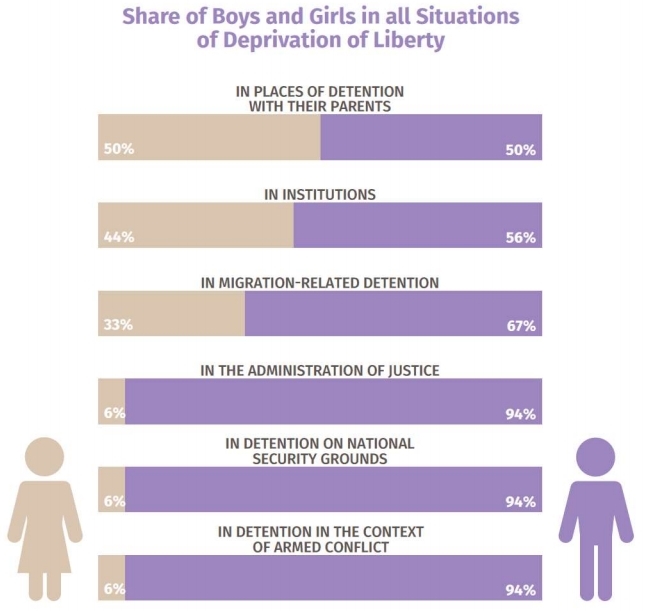

“The data collected for the study indicate significant gender disparities in the situation of children deprived of liberty. Altogether, there are far more boys deprived of liberty worldwide than girls. In the administration of justice and in the contexts of armed conflicts and national security, 94% of all detained children are boys; in migration detention the figure is 67% and in institutions it is 56%. The number of boys and girls who live with their primary caregiver (almost exclusively mothers) in prison is similar.”

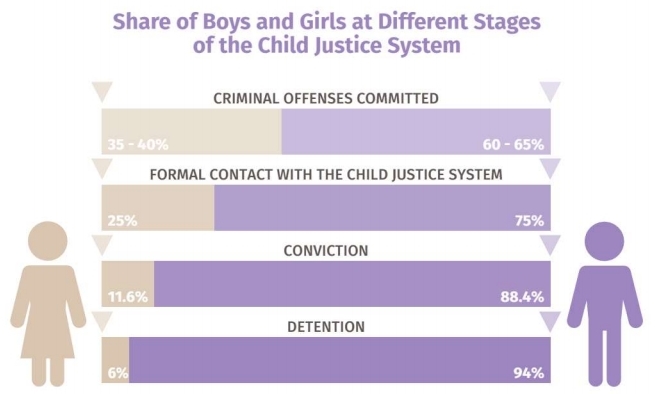

“Compared with the overall crime rate for children, the data gathered for the study show a tendency of the child justice system to be more inclined to apply diversion measures to girls than boys. While approximately one third of all criminal offences worldwide committed by children are attributed to girls, only 6% receive a prison sentence. There may be various reasons for this phenomenon. Most importantly, girls usually commit less violent offences and are more often accused of status offences. Girls are generally first-time offenders and more receptive to the deterrent effect of incarceration. Another explanation is the “chivalrous and paternalistic” attitude of many male judges and prosecutors in the child justice systems, who assume, according to traditional gender stereotypes, that girls are more in need of protection than boys.”

“Although most States allow convicted mothers to co-reside with their young children in prison, only eight States explicitly permit fathers to do so. Even in places where fathers as primary caregivers are allowed to co-reside with their children, there are (almost) no appropriate “father and child units” in the prisons, which means that there are practically no children co-residing in prison with their fathers.”

“Children from poor and socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, migrant and indigenous communities, ethnic and religious minorities and the LGBTI community, as well as children with disabilities and, above all, boys, are largely overrepresented in detention and throughout judicial proceedings.” (my emphasis)

“Deprivation of liberty constitutes a form of structural violence against children”

In view of the latter observation, and the overwhelming preponderance of boys in custody, can one not reasonably conclude that here we have an instance of gendered structural violence – against boys? And yet you will find no mention of this in the Istanbul Convention.

The complete report is “UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty” (Manfred Nowak, November 2019). The section on “Discrimination Against Boys” puts England and Wales amongst the top few countries in terms of gender ratio: “In some States, the percentage of boys detained in the context of the administration of justice is close to 98% (England and Wales, Argentina) or even 99% (South Africa, Georgia)”. Did we want to be in such company?

Almost all you need to know is the title of one of the report’s sub-sections,

“Penal System is the Most Gendered Institution in Society”

Quite.

What follows in that section is something I never thought to see in a report from the UN.

“Most research on the gender dimension of deprivation of liberty relates to the administration of criminal justice and primarily addresses cases of discrimination against girls, not against boys. Yet in 2006, Paulo Sergio Pinheiro noted that ‘millions of children, particularly boys, spend substantial periods of their lives under the control and supervision of care authorities or justice systems, in institutions such as juvenile detention facilities and reform schools.

According to research conducted by Bruce Abramson in the same year, the ‘penal system, adult and juvenile, is the most heavily gendered institution in society, even more so than the military, given current trends. He adds that the human rights movement, and the children’s rights movement in particular, is contributing to this male-female gender gap by discriminating against boys” (my emphasis)

It continues with this quote from Abramson,

“Whether we look at the CRC* movement, or at the broader human rights movement, or at the specialized juvenile justice advocacy, we find the same pattern of avoiding the gender dimension of juvenile justice. Some adults are in deep denial of the gender issue when boys are at the losing end of the disparities. But most people recognise that there is a gender issue. The problem is that no one has found an effective, positive way to address it. I think that juvenile justice professionals and CRC activists are paying a dear price in credibility for their failure to address gender: the public knows – at some level of awareness – that the advocates for reform are not addressing the problem when they duck the gender dimension of delinquency….Sad to say, there is outright sex discrimination against boys in the CRC movement.” (*CRC is the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child)

Wow! Let me just check this is really a UN report. But it may be significant that Nowak had to go back to research reported in 2006 for this evidence. He goes on to note,

“Although girls are less likely to commit serious criminal offences than boys, the detention rate does not reflect the crime rate. More than one-third (35-40%) of all criminal offences worldwide are attributed to girls. However, only one fourth of all children (25%) who come in formal contact with the criminal justice system are girls. Finally, only 11.6% of all convicted children are girls, and only 6% of all children who end up in detention are girls”

Nowak concludes that the data show that girls receive more lenient sentences, usually non-custodial, and tend to benefit from diversion away from custody through all the stages of the process. These observations are depicted in the graphics below.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The similarity with adult imprisonment in the UK is striking. It appears that neither age nor culture greatly ameliorates the huge sex-bias in incarceration. In the case of adults in the UK, we are surely long past any debate about the overwhelming male dominance in prison being largely due to discrimination; the progress of men and women through the UK criminal justice systems is remarkably similar to Figure 1. It is reasonable to suppose that discrimination is responsible also for the overwhelming preponderance of boys in the juvenile facilities.

Nowak’s chapter on gender issues ends in Recommendations which include this,

“Address over-representation of boys in detention by various means, above all by promoting diversions at all stages in the criminal justice system and by proportionally applying non-custodial solutions to boys, as it is more widely practised with girls.”

Who is going to hold the relevant UK Minister’s feet to the fire on this one?

It seems we have a way to go in some quarters. As of April 2018, there were 913 boys and just 27 girls in the secure estate in England & Wales (97.1% boys). In that month, Anne Longfield, the Childrens’ Commissioner for England, reported on a visit to some of these children “to learn about their lives before entering custody and understand the factors that led to them being imprisoned and what, if anything, could have been done to change their trajectory”. Well, very laudable. It’s exactly what a Children’s Commission should do. I have no difficulty with that…except that out of 913 boys and 27 girls…the 10 children she chose were all girls.