Part 1 of this blog dealt with the frequency of paternity fraud. In Part 2 we look at DNA paternity testing – and specifically how available it is within the UK.

The Legal Position

The issue of consent in DNA paternity testing is addressed in Section 45 of the Human Tissues Act (2004). Many sources give the false impression that it is illegal for a man to carry out a DNA paternity test without the mother’s permission. This is not true.

The Act makes it an offence to have human tissue with the intention of its DNA being analysed without proper consent. The maximum penalty for this offence is 3 years in prison.

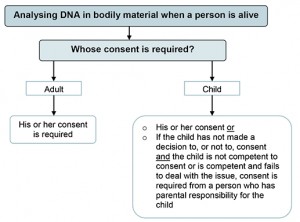

The legality of a DNA paternity test hinges upon consent. Qualifying Consent is defined in a flowchart, reproduced below, available on the Human Tissue Authority’s web site.

Essentially the man and the child must both consent. There is no requirement for the mother’s consent.

However, a very young child will not be deemed capable of consent. In this case the man may consent on the child’s behalf if he has parental responsibility (defined below).

There is no hard and fast rule regarding whether a child is capable of consent. I have seen advice suggesting that children of 12 and over are usually taken to be capable, but there is no guarantee of this – it will vary from case to case.

If the child is capable of consent but refuses consent, then holding material for the purposes of carrying out a DNA test would be illegal (quite rightly).

If the child is not capable of consent and the putative father does not have parental responsibility then a paternity test cannot be carried out unless consent is obtained from someone who does have parental responsibility, usually the mother.

However, my understanding is that the salient feature of the 2004 Act is that the man does not require the mother’s permission to carry out a DNA paternity test, providing that either the child is capable of consenting and consents, or, the child is not capable of consenting and the putative father meets the requirement as having parental responsibility and consents on the child’s behalf.

A man qualifies as having parental responsibility if, (i) he is married to the child’s mother, or, (ii) the child was born after 1st December 2003 and his name appears on the baby’s birth certificate.

But…the Act blurs what appears clear through this clause: “As the issue of paternity testing is a sensitive one, further guidance has been published by the Department of Health in this area.” I turn to this DH Code of Practice next – but note that such a document is not law, it is merely the guidance of one government department.

The Reality: The DH Code of Practice

Prior to the 2004 Act, the custom and practice in paternity testing was generally in accord with the Department of Health’s Code of Practice and Guidance on Genetic Paternity Testing in the UK (2001). This custom and practice is evident from the guidance on consent given by the testing laboratories. For example, Anglia DNA Services state that,

If a paternity Test is to be carried out for a child under 16 years, but the mother is not herself being tested*, then only the mother may consent for the child**

*It should be noted that at present the Child Support Agency require all three parties to be tested – ie mother, father and child. (Note that Dr Denise Syndercombe-Court confirms that they do not carry out DNA testing unless the mother consents)

** Following the changes which came into force in 2006 it is anticipated that these requirements will be modified when the ‘Code of Practice and Guidance for Genetic Paternity Testing Services’ (2001) has been revised in line with the new Act (it is currently under review).

From this one might have expected that the revision of the DH’s Code of Practice and Guidance on Genetic Paternity Testing would remove the requirement for the mother’s consent, thus bringing it into line with the 2004 Act. It does not. The relevant extract from the Department of Health’s Good Practice Guide on Paternity Testing Services (issue for Consultation/Discussion, February 2008) is,

3.33 The best interests of the child should be a primary concern when commissioning genetic paternity tests. This Guide reflects the view of the Human Genetic Commission that, in the majority of circumstances, motherless testing could prove harmful to the child, as well as to the family unit as a whole.

3.34 The British Medical Association advises doctors who are consulted by putative fathers about paternity testing without the mother’s knowledge and consent to encourage those seeking testing to discuss their plans with the child’s mother. Should the putative father reject this advice, the British Medical Association tells doctors not to become involved in the testing process.

3.35 We are aware too that, in cases where parentage is disputed, the Child Support Agency may offer genetic testing of all three parties – the child, the mother and the alleged father. It is unlikely that the Child Support Agency will accept motherless testing as a method of resolving a paternity dispute for the foreseeable future.

3.36 We are therefore of the view that motherless testing should not be undertaken by paternity testing companies, unless such a test has been directed by a court.

In Summary

All the influential bodies have capitulated to the feminist lobby and conspired to prevent men obtaining DNA paternity tests without the mother’s consent.

In doing so they are implementing restrictions on the rights of a man which have no legal standing.

The “best interests of the child” are being conflated with “the best interests of the mother” to spuriously justify this.

The claim that “motherless testing could prove harmful to the child” is based on no evidence or argument, it is merely asserted without reason. The reality is that it may prove harmful to the mother.

The Department of Health, the Child Support Agency (now the Child Maintenance Service), the British Medical Association and the Human Genetic Commission have taken it upon themselves to frustrate the legal entitlement of a man with parental responsibility to DNA paternity testing without the mother’s consent. There is no barrier to such a man doing so in the Human Tissues Act (2004). These Agencies appear to be preventing men accessing a legal right.

A man with parental responsibility may, subject to the child’s consent, carry out a ‘home’ paternity test with legal impunity. However, the authorities are unlikely to recognise such a test. The extra-legal restrictions imposed by the DH and the CMS prevent a man obtaining a test that will be recognised formally.

Finally, is there a catch 22 operating here? If a man has parental responsibility then he will, I presume, be liable to pay child maintenance irrespective of the result of a DNA test. On the other hand, if he does not have parental responsibility he cannot, without the mother’s consent, prove that he is not the father of a child incapable of consent – and hence may again be liable to pay child maintenance.