Feminists have an implacable determination to put more men in prison for rape. That objective is now being progressed by the SNP – well known for their upholding of strict personal standards.

In May 2021 my article The Myth About Rape Myths addressed the growing feminist determination to achieve more rape convictions by promoting the idea that jurors are unsuitable to make judgments on these sex offence cases. Mere lay persons, the hoi polloi, the riff-raff, the deplorables (that’s us) have not the wisdom to decide upon such matters. Any similarity to the reaction of the establishment to the Chartists’ petitions of the early nineteenth century is entirely apposite.

But what has that got to do with our recently ousted Lord Chancellor? I’ll come to that.

The feminists’ proposed policy on the matter revolves around either doing away with juries in rape trials, or subjecting juries to “training”. One knows who would do the “training”. No doubt the efficacy of such re-education would be confirmed by an assessment, with failure to demonstrate successful alignment with their views, however empirically false, leading to disqualification to sit on the jury. In short, such “trained” juries would be a sham, an obvious undermining of the principle that juries should be drawn, uncontaminated, from the public. Focus has, it seems, shifted to doing away with juries entirely in rape trials.

In happier times, one might have had confidence that Members of Parliament would have the wisdom, and historical appreciation, to protect jury trials with great passion. No longer. Feminism is now the dominant caucus across all Parties. Feminists have no truck with nasty patriarchal wisdoms. They can contemplate the abolition of juries in rape trials with nothing but approbation. But justice, like freedom, is indivisible. Feminists seem to have trouble understanding the message of “First they came for…”. You’d think that the TERFs’ taste of out-group status at the hands of the Woke-Trans might alert them to its relevance to themselves, but the great weakness of the ideological is their blindness to anything outside its restricted confines.

The point here is that, if you are inclined to dismiss this whole issue on the grounds that “why should I give a toss about rapists, the scum of the earth?” – the issue here is whether the accused are actually rapists. If you incline to the belief that women never lie about rape, then all that stands between you and a horrible awakening is an accusation. Do not be too confident that cannot happen: being innocent is not a guarantee. There are cases where a man ends up in court on a rape charge made by a woman whom he has never met. The percentage of rape allegations which are false is, perhaps, almost quantum mechanical in its uncertainty. I flatter myself that the best summary of the factual position is my 2022 review for the Male Psychology Magazine. The only thing one needs appreciate is that, regardless of the unknowable percentage, false allegations are not rare.

Consequently, in a decent society with a decent criminal justice system, it is essential that the rights of the accused (of rape or anything else) are protected. Irrespective of some people’s opinion to the contrary, it is a sound principle that it is better to let ten guilty men go free than to incarcerate a single innocent man (probably for 10 years or more). This is what “beyond reasonable doubt” is about. And, as barrister Matthew Scott has emphasised, scrapping juries in rape trials may well be the precursor to scrapping juries altogether – they are expensive, after all.

Moreover, with the CPS determined to subvert the disclosure process – the very problem that resulted in the collapse of some celebrated rape cases – the last thing our trial system needs is the abandonment of juries too.

To impose some patriarchal wisdom on you: when the criminal justice system becomes highjacked by a political power, you are on the path to tyranny, if not already there.

There was a so-called debate in Parliament on rape trials in 2018. It was not a debate but feminist MPs agreeing with each other. The line they were plugging then, and now, is that there is a widespread belief amongst the public – and hence amongst jurors – in myths about rape. The argument goes that belief in these myths causes juries falsely to find defendants not guilty. In my last article on this topic I quoted from Cheryl Thomas’s 2010 and 2020 reports which continue to have the only reliable data on juries’ belief in rape myths. (Thomas is Professor of Judicial Studies at UCL and Director of the UCL Jury Project).

Amongst other things, Thomas concluded in 2010 that conviction rates when the victim is male are consistently lower than when the victim is female, a fact that I subsequently confirmed (see Tables 19.4a-c of The Empathy Gap). This is worth noting because CPS data on rape convictions does not disaggregate by sex of victim – and, notoriously, the CPS VAWG reports classify male victims as victims of Violence Against Women and Girls (see here).

I’ll not burden this post with rape conviction statistics, though you can find a compilation in the Appendix of my last article, and some more recent data in the Appendix below. The other key conclusion from Thomas’s 2010 report was that “Juries are not primarily responsible for the low conviction rate on rape allegations”. The correctness of that is easily confirmed by the CPS data I give in the Appendix.

So, what is the Scottish Parliament up to? Well, as Stuart Waiton, lecturer at Abertay University, put it “the Scottish government, aided and abetted by the judiciary, is mounting an elitist assault on the justice system”.

Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC, Scotland’s top prosecutor, wants to introduce juryless trials for rape and attempted rape cases. She regards politicians to be “morally obliged” to consider it. Bain bases this opinion on the claim that research has shown that there is “overwhelming evidence” that jurors hold “prejudicial and false beliefs” about rape that affect their evaluation of evidence presented at trial, and that this research has found “considerable evidence of the expression of problematic attitudes towards rape complainers” among jurors. In other words, the usual “rape myths” argument.

The research Bain was referring to was that of Glasgow University’s Fiona Leverick, published in March 2021. Leverick has given a description of her research here. Leverick, with Glasgow University colleague Professor James Chalmers, and Professor Vanessa Munro of Warwick University, were commissioned to carry out the work by the Scottish Government. (Is that a paymaster who is neutral?). Here’s the key extract regarding how they acquired their data,

“The team used professional polling companies to recruit hundreds of volunteers, via public and door-to-door work. Videos of trials were made and mock juries were set up in buildings made to resemble courts.”

In other words, real jurors were not involved. The point is crucial because the November 2020 report by Cheryl Thomas contains a devastating critique of the use of such methods – of which Leverick must have been fully aware. The same newspaper report rightly alludes to this, quoting Tony Lenehan, president of the Scottish Criminal Bar Association,

“The research from Fiona Leverick and colleagues involved pretend jurors hearing pretend cases as the law doesn’t allow research with real jurors in real cases. Important academic voices add to our own doubts about the validity of this type of limited inquiry. It is disappointing to see the Lord Advocate embrace uncritically the stated findings of the mock jury work, where academic peers have expressed substantial misgivings….No type of High Court trial needs the input of our society more than rape trials….Jury-less trials in rape cases is a terrible idea. It seems to prioritise the voices of an emotionally invested minority, undermined by, rather than supported by, evidence and experience. It will dilute public confidence in justice and, in the long term, is likely to achieve the opposite of what it hopes.”

Quite. And there are plenty of other authoritative legal voices speaking out against this feminist crusade (e.g., here, , here, and here and Lenehan again here). But there were plenty of authoritative medical voices speaking out against the Government’s Covid-19 impositions, but to no avail. Dorothy Bain’s wishes appear to have triumphed. Lady Dorrian’s review has provided the basis for the SNP Government to instigate the pilot juryless trial system, which appears now to have the green light.

And so, at last, to the 2020 report by the UCL Jury Project led by Professor Cheryl Thomas. It is such an emphatic demolishing of the Bain-Dorrian-Leverick feminist position that I quote it at some length. Thomas starts with an historical allusion to a famous 1670 precedent,

“In Bushell’s Case, the four jurors who refused to be coerced by the judge into returning a guilty verdict of unlawful assembly against Penn and Mead were accused of being Dissenters who were biased against the liturgy of the Anglican Church. Their refusal to convict the defendants for breaches of the Conventicle Act was attributed to this, although there was no concrete evidence to support these claims of juror bias.

The 21st century jury in England and Wales has recently come under attack on the grounds that jurors are biased against complainants in rape cases and refuse to convict defendants in rape and sexual offences cases because they believe myths and stereotypes about rape and sexual behaviour. Until now there has been no empirical evidence based on research with real jurors at court in England and Wales to either substantiate or refute these claims. But this has not deterred the making of assertions about jury bias in rape and sexual offences cases, including calls for the removal of juries in rape cases. None of these claims were based on any research with actual juries in England and Wales. Instead they have relied on public opinion polls, a single study that used students and volunteers to act as proxy (“mock”) jurors and anecdotal views of prosecutors in rape cases who were asked post-acquittal why they thought they did not achieve a conviction in their cases.

Despite the lack of any empirical evidence from research with real jurors, these claims led to a petition to Parliament in 2018 calling for ‘All jurors in rape trials to complete compulsory training about rape myths’.”

Thomas goes on to deconstruct the claims being made in support of that 2018 petition concluding that “the petition’s claim that research showed jurors accepted commonly held rape myths and did not understood judges’ directions on these myths could not have been correct”.

I believe these remarks pre-dated the publication of Fiona Leverick’s Glasgow research – but note that Leverick’s research was also based entirely on mock juries not real ones.

Thomas’s report goes on to observe,

“It is unclear what the source could be of the statistic cited (in association with the 2018 petition) that the conviction rate in rape trials is 21 per cent lower than other crimes. Detailed research on all jury verdicts in all courts in England and Wales over a substantial period of time had already shown that juries convict in rape cases more often than they acquit, and that the jury conviction rate in rape cases is higher than it is for other serious crimes such as attempted murder, GBH, and threatening to kill.”

Anomalously low conviction rates continue to be cited by those promoting the Bain-Dorrian-Leverick feminist position, namely they claim that the conviction rate for those rape cases that reach court is 43% compared to 88% for all crimes (see here and here). In the Appendix I present CPS data which shows the 43% figure to be incorrect and instead supports the Thomas position, quoted above.

However, the beneficial spin-off from that 2018 petition, and the associated monoculture of (feminist) opinion expressed in Parliament, was the commissioning of Thomas’s new research.

The UCL Jury Project undertook research in 2018–19 based on real juries and real trials, immediately post-verdict. A total of 65 discharged juries (771 jurors) in 4 different court regions took part in the research. The cases the juries tried covered a range of offences, including sexual and non-sexual offences. There was a 99 per cent participation rate. The findings regarding what jurors really believe were,

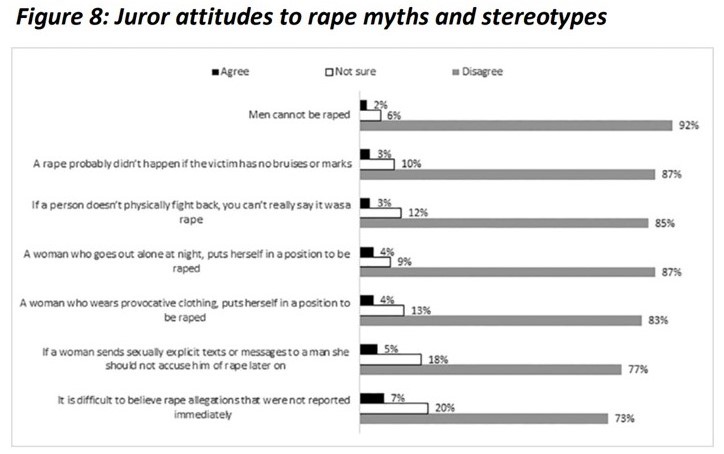

“…hardly any jurors believe what are often referred to as widespread myths and stereotypes about rape and sexual assault. The overwhelming majority of jurors do not believe that rape must leave bruises or marks, that a person will always fight back when being raped, that dressing or acting provocatively or going out alone at night is inviting rape, that men cannot be raped or that rapes will always be reported immediately. The small proportion of jurors who do believe any of these myths or stereotypes amounts to less than one person on a jury.”

Figure 8 of the Thomas report is worth a look to see just how very emphatic is that conclusion…

One area where Thomas identifies some additional guidance to juries might be beneficial is in respect of emotion displayed by complainants when giving evidence. She writes,

“..research has confirmed that the amount of emotion displayed by a rape victim when recounting a rape can vary substantially, and this reflects more widespread aspects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).”

43% of the jurors said they would expect a complainant to be very emotional when giving evidence about a rape, while 22% said they would not expect this and 35% were uncertain on this issue. Thomas interprets this as a sign they would benefit from additional guidance. Perhaps so, but how would you answer the question “I would expect anyone that was raped to be very emotional when giving evidence in court about the rape” assuming you knew the empirically correct answer is “very variable” – given that the options were only “agree, disagree, or not sure”? You could reasonably opt for “not sure”, on the grounds that, indeed, one cannot be sure. It’s a badly posed question.

However, this is a minor point. Thomas sums up the implications of the UCL research thus,

“This first ever empirical research assessing the attitudes of actual jurors serving on real cases in England and Wales reveals that the claim made in the petition to Parliament that “Research shows that jurors accept commonly held rape myths resulting in many incorrect not guilty verdicts” is incorrect. The research also reveals that previous claims of widespread “juror bias” in sexual offences cases are not valid. Jurors at court do not hold the same views on these issues as reported in public opinion polls and “mock” jury research using students and volunteers. For example, a December 2018 End Violence Against Women survey reported that 33 per cent of Britons said there must be violence for rape to occur. But the UCL Jury Project research conducted with actual jurors shows that only 3 per cent of jurors said rape had to result in bruises or marks and only 3 per cent of jurors said it was not rape unless a person fought back. Not only does this demonstrate that public opinion polls cannot be a proxy for what real jurors believe, but the small percentages of real jurors who believed these rape myths amounted to less than one person on any jury.”

Thomas et al then go on to ask why it is that mock juries and opinion polls are so unrepresentative of real juries. The answer is simple: sample bias. Thomas asked 1,175 jurors whether, if jury duty had been voluntary, they would have chosen not to serve. The answer was 87% of them would not have served on the jury. So, by using volunteers in mock juries one is sampling an uncharacteristic 13% of the population (at best, assuming there are no other biases in the sampling, which, as anyone who has conducted survey research knows well, is darned hard to avoid).

So, there we have it – Thomas’s research provides the only reliable data on the issue of juries believing rape myths. Data based on mock juries is known to be grossly unreliable. The valid outcome of the UCL work is that the widespread belief in rape myths is a myth.

[Incidentally, Thomas’s jurors went on to benefit considerably from their experience as jurors, despite most being initially reluctant].

So – what about Dominic Raab, then – our recently ousted Lord Chancellor, Secretary of State for Justice and Deputy Prime Minister? For foreign readers, Rabb was obliged to resign following allegations of “bullying”. An independent review by a KC cleared him of all but two “charges”. As Rabb said in his resignation letter, setting the threshold for bullying so low is a dangerous precedent. For years we have seen inconvenient politicians being removed from Parliament by allegations of sexual misconduct (apparently a man cannot touch even another man without it being “groping”). This provides yet another mechanism for the removal of those with Incorrect views.

As Brendan O’Neill wrote in The Spectator, “I know the story is that he was a monster in his various departments, allegedly barking instructions and wagging a finger at his stressed-out minions. But the anti-Raab revolt smacks far more of bullying to me. Civil servants clubbing together to drum an exacting minister out of his job? It definitely has a whiff of Mean Girls to it.” O’Neill has it right – Raab was just doing his job, dealing firmly with civil servants who jolly well needed it.

Raab must surely have been in the sights of the progressives for a long time. Here are a few of his sins (sources here, here and here). He thought there should be a consistent standard in regard to sexism against either men or women. He actually had the nerve to say that some feminists were now amongst the most obnoxious bigots – and repeated it when challenged. Raab highlighted the wide range of sex discrimination he said was faced by males including anti-male discrimination in rights of maternity/paternity leave, young boys being educationally disadvantaged compared to girls, and how divorced or separated fathers are systematically ignored by the courts. He claimed (rightly) that from the cradle to the grave, men are getting a raw deal. Men work longer hours, die earlier, but retire later than women (this being before the state pension age reforms).

These remarks were early in his career, but the progressives do not forgive or forget. His cards were marked.

But it was Raab’s pressing for a UK Bill Of Rights that I suspect led to his removal being a high priority for progressive axis. This Bill, if enacted, was intended to replace the Human Rights Act. That’s bad enough from the left’s perspective. But there’s worse. It would also have ended the duty on UK courts to take into account the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, a body which Raab was right to emphasise has no legislature (and hence, by implication, no legitimacy). We’ll make crystal clear, Raab has said, that the UK Supreme Court, not Strasbourg, has the ultimate authority to interpret the law in the UK.

Oh dear, that’s rather too much “taking back control”, isn’t it? Well, Raab was a leading light in Brexit.

The Bill of Rights would also strengthen the right to freedom of speech, another area which the progressives regard as merely “right wing” (oddly). So, you see, Raab’s crimes are many and deep.

But of relevance to this article, Raab’s Bill Of Rights would also have enshrined in primary legislation the right to trial by jury in England and Wales. Rabb wrote in The Times “Trial by jury is another ancient right, applied variably around the UK, that doesn’t feature in the ECHR (European Court of Human Rights), but will be in our bill of rights”.

Raab duly sponsored the Bill of Rights on 22 June 2022 which progressed only as far as its second reading in the Commons before Liz Truss, briefly prime minister, shelved it last year. But under the new Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, Dominic Raab regained his post. As would be anticipated, the Bill of Rights was back on the agenda. In the state opening of parliament in 2023, it was indeed announced that the Bill would be brought back.

On 28 March 2023, the law blog Law Pod UK quoted Raab as stating that the Bill of Right was “ready to go”.

A few weeks later, he was gone.

What happens to the Bill of Rights now remains to be seen. However, it looks hopeful. The new Lord Chancellor and Justice Secretary, Alex Chalk, appears to back it – at least if the contents of his web site as a constituency MP is any judge. On that site he appears to support the Bill, though there’s no saying how he may modify it from Raab’s version. However, of note for this article, he states: “it will also recognise that trial by jury is a fundamental element of fair trials in the UK”. So far, so good. Perhaps England and Wales will escape the debacle descending upon the Scots. But the vultures are now circling to put pressure on Chalk to ditch the Bill. The live poll at the end of that Sunday Times article puts at 79% the public vote to scrap the Bill. Quelle surprise, eh?

Appendix: CPS Data on Rape Convictions

I use the following sources,

- CPS conviction data VAWG Prosecution-Crime-Types-Data-Tables-Year-Ending-June-2022.xlsx (live.com)

For the year ending 30 June 2022, Table 2.2 of the first source gives these data for rape prosecutions,

| Outcome Category | Outcome % |

| % Convictions | 69.0% |

| % Guilty Pleas | 39.8% |

| % Convictions after Trial | 29.2% |

| % Proved in Absence | 0.0% |

| % Non-Convictions | 31.0% |

| % Prosecutions Dropped | 9.3% |

| % Acquitted/Dismissed after Trial | 18.9% |

| % Administratively Finalised | 2.8% |

| % Discharged | 0.0% |

It is hard to recognise the 43% figure quoted by the pro-Bain/feminist sources quoted above. Note that these data confirm Thomas’s claim that rape juries convict (29.2%) more than they acquit (18.9%).

For other sexual offences excluding rape, the overall conviction rate (Table 4.2) was 83.7%.

The second source gives, for the same period (year ending 30 June 2022) the conviction rate for all sex offences to be 80.9%. This compares with 80.6% for homicide, and 79.4% for crimes against the person (which will include violence against the person, e.g., GBH, ABH, etc). So, those conviction rates are comparable. Though the conviction rate specific to rape is somewhat lower, it is not dramatically so – and it is unsurprising that it would be given the unique difficulties with the nature of the offence.