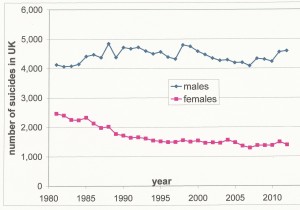

In 1981, 2, 466 women in the UK took their own lives. Three decades later the number in 2012 had almost halved to 1,391 (Ref.[1], see above graphic). In 1981, 4,129 men in the UK took their own lives. Three decades later the number in 2012 had risen to 4,590. Males are now 77% of suicides, women 23%.

Why?

Perhaps the reduction in female suicides could be thanks to improvements in health care, including psychiatric care, plus a range of suicide prevention barriers as well as social, political and personal empowerment.

Are we to conclude that none of these improvements apply to males?

To put these figures in perspective, considering just England and Wales, there were 3,740 male suicides and 1,101 female suicides in 2012 compared with 15 men and 76 women killed by partner violence last year, and a total number of homicides of 380 men and 171 women. Clearly suicide is a far bigger killer than either partner violence or homicide in general. And it is mainly men that are dying.

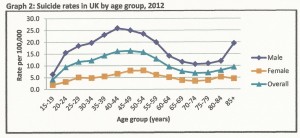

The graph below, from Ref.[2], shows that there is a marked peak in men’s suicide rate in the age range 40 to 50. It is not just younger men killing themselves. It is men whose misery has, it appears, reached a certain maturity. In Wales and Scotland the suicide rate peaks for somewhat younger men at an alarming 40 per 100,000, and in Northern Ireland the peak is 50 per 100,000 (Ref.[2]).

But it is in men’s prisons that suicide truly peaks. From Ref.[3] we learn that, “between January 2013 and 2 October 2014, 134 adults, including four women, killed themselves in prison”. (Aside: Regular readers of this or similar blogs will note the wording – I paraphrase “130 monkeys and 4 real human beings”). In financial year 2013/14 there were 88 self-inflicted deaths in UK prisons. For men this amounts to a rate of about 93 per 100,000, more than six times the UK average.

The latest data indicate that the suicide rate in men’s UK prisons is the highest for many years (Ref.[3]). Ministry of Justice figures show that whilst deaths are up in men’s jails they are down in women’s facilities (Ref.[3]). The latter has been attributed to improved safety measures as a response to the recommendations of the Corston Report.

I have had occasion to excoriate this report previously (Ref.[4]). It is one of the most egregious examples of partisan compassion to come out of governmental sources (and that is saying something). This is the report that contains one of my all-time favourite feminist quotes: “equality does not mean treating everyone the same.” The thrust of Baroness Corston’s report is that we really should not treat women prisoners the way we treat men prisoners – because, well, that’s too horrible. In contrast to female prisoners, Baroness Corston does not consider compassion towards male prisoners to be necessary. That’s a shame because it would appear that the result is an increasing suicide rate. Who would have guessed?

But I digress. The purpose of this post is to examine what is being done to identify the reasons for men’s high suicide rate in the population at large, and what is being done to prevent it.

You will guess the answer. But let’s examine the smoke screen first.

Ref.[5] sets out the government strategy for suicide prevention. Its overall objective is a reduction of the suicide rate in the general population, and specifically reducing the risk of suicide in key high-risk groups. It states that,

We have identified the following high-risk groups who are priorities for prevention:

- young and middle-aged men

- people in the care of mental health services, including inpatients

- people with a history of self-harm

- people in contact with the criminal justice system

- specific occupational groups, such as doctors, nurses, veterinary workers, farmers and agricultural workers.

So far, so good. Men, as the obvious demographic, accounting for 77% of suicides, have been identified. But later it states,

This strategy identifies the following groups for whom a tailored approach to their mental health is necessary if their suicide risk is to be reduced…..

and goes on to list demographics non of which are “men” or even specifically male, with the exception of “veterans”. I was pleased to see “veterans” listed. But, confusingly, later in the report we read this,

In general, suicide rates among armed forces veterans are lower than those in the general population. There is no evidence that, as a whole, people who have served their country in armed conflict are at higher risk of suicide.

So, it appears that veterans are not a target group for assistance either. What we do find later in the document is the following,

- Timely identification and referral of women and children experiencing abuse or violence, so that they are able to benefit from appropriate support.

- Call to End Violence against Women and Girls (2010), a cross-government strategy, has been followed by two cross-government action plans –

- The Royal College of General Practitioners has produced an e-learning resource for GPs to enable them to identify and respond to victims of domestic violence more effectively.

- Southall Black Sisters have developed a model of intervention on domestic violence amongst Black and Minority Ethnic women.

It seems not to have crossed the authors’ minds that, if partner violence plays a role in causing suicide, then men, as the majority of suicide victims, might also “benefit from appropriate support“. This is despite the fact that there is evidence from the USA that domestic violence does indeed result in significant numbers of male suicides, Ref.[6].

What I was particularly interested in was the issue of suicide rates in men following partnership break-up. There is a degree of recognition of this in Ref.[5], as the following extracts illustrate,

- Stressful life events can also play a part. These include…..family breakdown and conflict including divorce…

- Factors associated with suicide in men include…..family and relationship problems including marital breakup and divorce….

A very obvious piece of required research is to discover if suicides peak, in men or women, after partnership break-ups.

However, whatever is written in Ref.[5] matters little. What matters is what is actually being done. At this point we discover that very few of the issues discussed in the Strategy document have actually resulted in action. This emerges more clearly from,

Ref.[7]: “The Policy Research Programme is currently investing £1.5m over three years into six suicide-related projects. They cover self-harming behaviour, the situation of LGBT youth and the role of the internet and social media in relation to suicidal behaviour.”

Ref.[8]: “Suicide prevention strategy backed by £1.5m. Funding will be used to look at how the number of suicides can be reduced among people with a history of self-harm. Researchers will also focus on cutting suicides among children and young people and exploring how and why suicidal people use the internet.”

These sources are consistent, though when I searched the Policy Research Programme, Ref.[9], I found only the work programme on self-harm, namely that led by Professor Keith Hawton at Oxford. However, I believe the bottom line as regards what is actually being done can be discerned from the Invitation to Tender, Ref.[10]. This calls for tenders against the budget of £1.5M in five areas,

- How to reduce the risk of suicide in a key high-risk group: People with a History of Self-harm

- How approaches and interventions can be tailored to improve mental health in specific groups

- How self-harm can be better managed and suicide reduced in children and young people, including looked-after children and care leavers

- How the media can be better supported in delivering sensible and sensitive approaches to suicide and suicidal behaviour

- How the health and social care system can provide better information and support to those bereaved or affected by a suicide.

Incredible. Five areas of action and not one even mentioning men as the demographic resulting in 77% of suicides.

There is evidently no curiosity to discover why male suicides are so high – and specifically so in the 40-50 age range.

No research has been advised to investigate the impact of either domestic violence or partnership break-up on male suicide.

And the appalling rate of suicide in men’s prisons is ignored, despite the knowledge of interventions which have been successful in women’s prisons.

One is bound to ask: is this neglect of men deliberate policy or because compassion for men as a group simply does not occur to the people responsible?

If you were charged with reducing the suicide rate, wouldn’t you want to tackle the demographic which leads to 77% of suicides? Would you perhaps start by identifying the reasons?

Perhaps they do not want to know the reasons. Perhaps they are frightened to pull at this loose thread in case what it unravels is the entirety of the men’s rights grievances, such as listed on the home page?

The situation is no better in other countries. Steve Brule, Ref.[11], notes that a whole string of bodies authorised to address suicide in the USA and Canada simply fail to mention at all that the overwhelming majority of victims are male. Avoiding focussing on this fact means avoiding having to ask “why?”. Tellingly, as Steve observes, surveys of well-being report that “in most advanced countries women report higher satisfaction and happiness than men” and “women around the world are happier than men, regardless of which happiness question is used” and “women are relatively happier in countries where gender rights are more equal”. It is hard to avoid the temptation of suggesting the logical negative of this: that men are less happy where they are less equal, and perhaps this is not unrelated to their high suicide rate?

On mentioning the high male suicide rate, many people will reply that women attempt suicide more often. Statistics on attempted suicide are harder to acquire. For one thing, it is not clear if an instance of self harm is actually a suicide attempt. For another, no statutory body is charged with collecting the data. Perhaps the best guidance on attempted suicide and self harm is from the Oxford group, whose latest report is Ref.[12]. The Group collates information on all cases of self-harm presenting to the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford. They have been doing so since 1976. The latest report indicates the following,

- The sex ratio of people presenting with self-harm was 1.4 women to each man in 2010;

- In 2011 there was a large increase over 2010 in males (+11.2%); the numbers of females showed a small decrease (-1.2%). This continues the trend of recent years;

- On average each person presented 1.4 times (negligible difference between genders);

- Of all self-harm episodes 70.7% involved self-poisoning;

- Suicide intent scores (a measure of the extent to which patients truly wished to die) were in the high or very high range in 28.1% of assessed episodes;

- Attempted suicides, unlike successful suicides, can be asked the reason. What emerges does not show very marked differences between the sexes, as shown by the Table below,

| Reason | males | females |

| partner | 41.9% | 39.4% |

| employment/studies | 34.5% | 27.1% |

| alcohol | 34.2% | 22.9% |

| other family member(s) | 30.1% | 42.6% |

| finances | 27.6% | 19.7% |

References

- Office for National Statistics, “Suicides in the United Kingdom, 1981 to 2012”, February 2014, http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-332358

- Elizabeth Scowcroft, “Suicide Statistics Report: Including data for 2010-2012”, Samaritans, March 2014,

- http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/oct/21/prisons-inspector-suicide-understaffing-overcrowding-mental-health-vulnerable-inmates?CMP=twt_gu

- http://redpilluk.co.uk/CrimeAndPunishment.pdf

- Preventing suicide in England: A cross-government outcomes strategy to save lives, HM Government, Mental Health and Disability Division, Department of Health, 10 September 2012.

- Richard Davis, (2010) “Domestic violence?related deaths”, Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, Vol. 2 Iss: 2, pp.44 – 52.

- http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/feb/20/britain-male-suicide-rate-tragedy-failure

- http://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/sep/10/suicide-prevention-strategy

- Projects, initiatives and long-term programmes of research currently funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme, October 2011, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20131103140330/http://prp.dh.gov.uk/2011/10/21/prp-commissioned-projects-aug-20/

- Department of Health Policy Research Programme, Invitation to Tender, Research Initiative to Support the Implementation of the National Suicide Prevention Strategy.

- http://www.avoiceformen.com/men/world-suicide-and-the-world-happiness-report/

- Keith Hawton, Deborah Casey, Elizabeth Bale, Dorothy Rutherford, Helen Bergen, Sue Simkin, Fiona Brand and Karen Lascelles, “Self-Harm in Oxford 2011”, Oxford Centre for Suicide Research.