It is well known that the family courts are a meat grinder for men (yes, and sometimes for women, but mostly for men). Here I examine an aspect of recent history to expose one important mechanism of this meat grinder: the role played by allegations of domestic violence, and in particular its connection with access to legal aid. As usual on mra-uk, you will find that this post is driven by data, not opinion. I gratefully acknowledge certain individuals as the source, via FOI, of some of the data quoted.

Readers will be inclined to think that I am a bitter man with a chip on my shoulder and a history of being harshly treated by the family courts. Not so. I have been married for 34 years, never divorced and have no personal experience whatsoever of the family courts or child custody issues. Nor has anyone in my extended family, not my parents, nor my wife’s parents, nor our two sons, nor our respective siblings or their offspring. I am disinterested other than as directed by the facts.

Contents (click on links to go to that Section)

- Public and Private Law and LASPO

- The Domestic Violence Gateway

- LASPO and the Allocation of Legal Aid by Sex

- Divorce Rate and DV Rate

- Numbers of Injunctions for DV

- Proportion of Family Cases Involving DV

- False Allegations Before LASPO?

- NMOs by Sex of Applicant

- What Path Through the Gateway?

- Numbers of NMOs by Region

- NMOs Issued by specific Designated Family Justice Areas (DFJA)

- Abusers Cross-Examining Victims

- Conclusions

1. Public and Private Law and LASPO

First let’s get some legal jargon out of the way: public family law versus private family law. Public family law cases are those brought by local authorities or an authorised body (e.g., the NSPCC). The purpose of public family law is to protect children. Examples of public family law include applications for care orders or supervision orders, or addressing adoption issues. In contrast, private family law typically addresses issues such as divorce and the resulting disputes over arrangements for children.

As a result of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders (LASPO) Act 2012, the rules for determining the availability of legal aid were changed. These new rules came into force on 1st April 2013, being administered by a new executive agency of the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) called the Legal Aid Agency (LAA). Legal aid continues to be available for public family law cases. But under the new rules, legal aid funding is no longer available, in general, for private family law cases. However, private family law cases involving domestic violence (DV), forced marriage, child abuse or child abduction do continue to receive funding for legal aid. It is the DV exception to the withdrawal of legal aid in private family law which is the focus of this investigation.

Legal aid is usually subject to means testing. However, there is again an exception. The LAA waives the means test in the case of applications for legal aid for an order for protection from domestic violence or forced marriage.

2. The Domestic Violence Gateway

The “domestic violence (DV) gateway” is the term used to describe the route by which legal aid may be claimed in private law cases where domestic violence is alleged.

In criminal cases one thinks of legal aid as being provided to the defendant in order that he may have professional legal representation to facilitate his defence. Oddly, in the case of the DV gateway, it is the person making the accusation who receives the legal aid, not the accused. This has led to a pernicious situation arising in respect of the accused potentially having no professional representation or assistance to facilitate his defence against an accuser who is so represented (see Section 11 below).

In 2015 a parliamentary Justice Select Committee held an inquiry into the impact of changes to civil legal aid under LASPO. In its submission to the inquiry the MoJ summarised the types of evidence needed to activate the DV gateway as follows,

- a conviction, police caution, or ongoing criminal proceedings for a domestic violence offence;

- a protective injunction;

- an undertaking given in court (where no equivalent undertaking was given by the applicant);

- a letter from the Chair of a Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC);

- a finding of fact in court of domestic violence;

- a letter from a defined health professional (which includes a doctor, nurse health visitor or midwife);

- evidence from social services of domestic violence; and,

- evidence from a domestic violence support organisation of a stay in a refuge.

Evidence, except for convictions, was subject to a 2 year time limit prior to April 2016.

The system was reviewed in early 2013 and new regulations were brought into force in April 2014 which extended the types of evidence accepted to include,

- police bail for a domestic violence offence;

- a bindover for a domestic violence offence;

- Domestic Violence Protection Notice/ Domestic Violence Protection Order;

- evidence of someone being turned away from a refuge because of a lack of available accommodation;

- medical evidence expanded to include evidence from practitioner psychologists; and,

- evidence of a referral to a domestic violence support service by a health professional.

A further review led to more changes which came into force in April 2016, the most significant of which was the extension of the evidence period from 2 years to 5 years.

It would take us too far from our present purpose to critique the security of these sources of so-called ‘evidence’, tempting though it is to do so. I make just a couple of observations,

- It does not take an acute legal mind to distinguish between applying to a refuge and objective evidence of another person’s guilt. And the impartiality of some of the parties who are granted the power to create ‘evidence’ is, to put it mildly, questionable.

- Following an allegation of domestic violence, it is common practice for a man’s solicitor to advise that he sign an “undertaking”, as in item (iii), stating that he will not threaten, harass, intimidate or pester his ex (or other such wording as appropriate), see here for example. This is advised on the grounds that the alternative is a more high risk strategy involving asking a judge to make a ruling on the matter, which may end up with the man being ruled as a DV perpetrator. Solicitors may convince a man to go down the “undertaking” route on the grounds that there is no admission that his ex’s allegations are true. What the man is likely to be unaware of is that, by doing so, he has just provided his wife with legal aid to deploy against him.

The coup de grace is this additional ruling,

Legal aid is also available for proceedings which provide protection from domestic violence, such as protective injunctions, without the need to provide evidence of domestic violence.

Consequently an application for a protective injunction following from an allegation of domestic violence will be funded by legal aid, without means testing and without any need for evidence. Upon such an injunction being granted, the injunction itself then provides ‘evidence’ for the granting of further legal aid in the private family law proceedings, e.g., over child arrangements. To the lay person this seems like a well funded mechanism for creating ‘evidence’ out of thin air.

What could go wrong?

3. LASPO and the Allocation of Legal Aid by Sex

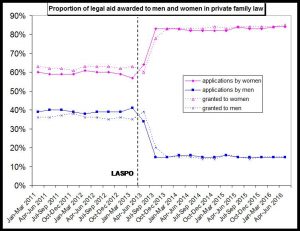

The immediate answer to that question is provided by Figure 1. This shows the breakdown by sex of legal aid applications and awards in private family law. Clearly the introduction of LASPO has driven a huge reduction in the relative availability of legal aid to men in private law cases. Prior to LASPO the split was roughly 40%/60% to men and women respectively. Post-LASPO it is now 15%/85%. That LASPO is the cause of this change is entirely unambiguous.

Figure 1 Legal Aid Provision in Private Family Law by Sex of Applicant (Data provided by LAA Statistics, 21/10/16, private communication to FNF-BPM) Click to enlarge

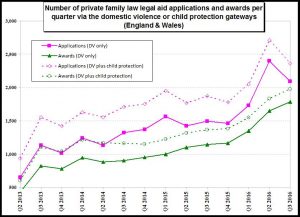

If the world were populated entirely by scrupulously fair people who never allowed their emotions or their self-interest or their cultural biases to dictate their behaviour, no doubt LASPO would cause no difficulty, Meanwhile, back on this planet, one does not need to be especially cynical to suspect that allegations of domestic violence might become more frequent following the withdrawal of legal aid from private law cases unless such an allegation is made. Figure 2 shows how the number of legal aid applications, and awards, using the domestic violence gateway has surged in the four years since LASPO. There are now 3 to 4 times as many applications, and awards, for legal aid citing DV as their basis than there were in mid-2013.

Figure 2 Data from “Legal Aid Statistics: July to September 2016” Tables 6.8 and 6.9 Click to enlarge

Before examining the statistics of DV allegations in family law in more detail, is there an explanation of Figure 2 other than it being evidence of abuse of the system via false allegations? Two questions may have arisen in the reader’s mind in this context,

- Could Figure 2 be a consequence simply of the increasing number of divorces?

- Could Figure 2 be a consequence of the increasing incidence of DV generally?

The answer to both these questions is no, as we see next.

4. Divorce Rate and DV Rate

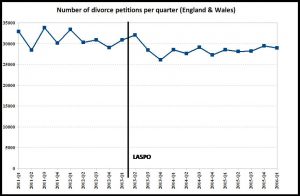

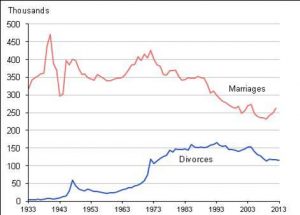

Evidence that the answers to the above questions are indeed ‘no’ is provided by Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3a shows that the number of divorce petitions has, in fact, reduced since LASPO. Indeed, Figure 3a seems to suggest that LASPO itself might have reduced the number of divorces, though there has been a downward trend for some time, as shown by Figure 3b, so this may be illusory.

Figure 3a Click to enlarge

Figure 3b Annual rate of divorces (England & Wales) Click to enlarge

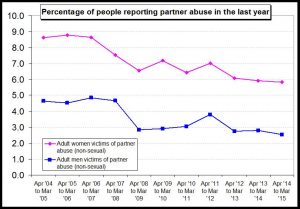

The Crime Surveys for England & Wales (CSEW) are generally believed to be the best indicators of the incidence of domestic violence. Figure 4 shows the percentage of people reporting DV in the preceding year. The rate of DV has been falling, not increasing (despite the impression you might get from the media).

Hence, the dramatic increase in the applications for legal aid via the DV gateway, Figure 2, is in spite of a falling divorce rate and a falling DV rate in the population as a whole.

Suspicion that Figure 2 is driven by an increasing rate of false allegations can only deepen.

Figure 4: Partner abuse frequency in the general population from CSEW surveys (Data from Focus on: Violent Crime and Sexual Offences, year ending March 2015, Bulletin Tables, Figures 4.3 and 4.4) Click to enlarge

5. Numbers of Injunctions for DV

Injunctions for DV ordered by the family courts are of two types: non-molestation orders (NMOs) and occupation orders. The latter relates specifically to who is allowed to reside in the home in question (regardless of ownership) and may also prohibit the respondent (the person against whom the injunction is taken) from entering a specified area in the vicinity of the home. Non-molestation orders are to protect victims of domestic abuse and the specific terms of the order vary. Typically the injunction will seek to stop the abuser from being violent towards the victim(s), either physically or by threatening and intimidating. Commonly the order will prohibit the respondent from communicating in any way with the person who obtained the Order against them.

Substantially more NMOs are awarded than occupation orders.

Both types of injunction may be made either ex parte or ‘on notice’. The former relates to an order made by the court at the request of the applicant but without the respondent being present, or even initially aware of the order until he is informed later. Conversely ‘on notice’ injunctions are considered by the court only after the respondent has been given notice of the application (perhaps with the option of being present during the ruling).

More injunctions are served ex parte than on notice.

Thus a man served with a NMO may find himself legally barred from even ‘phoning, or writing to, his wife or his children. In the case of ex parte orders, the man may not initially know what allegations have been made against him.

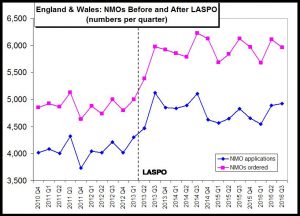

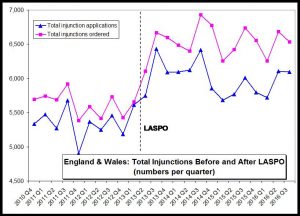

The quarterly number of NMOs before and after LASPO are shown in Figure 5, whilst Figure 6 shows the total number of injunctions (NMOs plus occupation orders). There is an obvious increase in the number of injunctions ordered after LASPO. An elementary statistical test shows that the change in the rate of issuance of injunctions before and after LASPO is significant at the 99.9% confidence level, i.e., it is not mere statistical noise.

Over England and Wales as a whole, averaging over the nine quarters before LASPO and the 12 quarters after LASPO, the number of NMOs awarded increased by 20%. We will see below that even greater percentage increases in awarding NMOs are apparent in some parts of the country.

To recap: the rate at which DV related injunctions were issued increased after this became a route to the acquisition of legal aid.

Figure 5 (Data taken from Family Court Statistics Quarterly, July to September 2016, Table 14)

Figure 6 (Data taken from Family Court Statistics Quarterly, July to September 2016, Table 14)

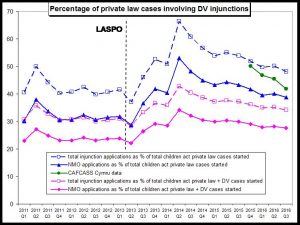

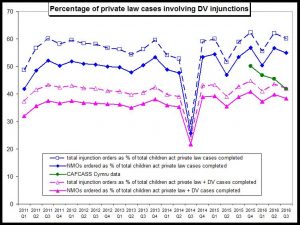

6. Proportion of Family Cases Involving DV

The same source of data which provides Figures 5 and 6, the Family Court Statistics Quarterly, July to September 2016, also provides the total number of cases under the Children Act in private family law in England & Wales (see Table 1 of this reference). Data are given for both the number of cases starting and the number completing. Dividing the number of DV injunctions by the number of private law ‘children act’ cases plus DV cases provides the proportion of all relevant cases in which DV injunctions are requested/granted. The results are plotted in Figures 7a and 7b which show,

Figure 7a (starting position)

- NMO applications as % of total children act private law plus DV cases started;

- Total injunction applications as % of total children act private law plus DV cases started;

- NMO applications as % of total children act private law cases started;

- Total injunction applications as % of total children act private law cases started.

Figure 7b (final position)

- NMOs granted as % of total children act private law plus DV cases completed;

- Total injunctions granted as % of total children act private law plus DV cases completed;

- NMOs granted as % of total children act private law cases completed;

- Total injunctions granted as % of total children act private law cases completed.

Also shown on Figures 7 are some Welsh data obtained from CAFCASS Cymru.

Figure 7a clearly shows the effect of LASPO in increasing the percentage of cases in which applications are made for DV injunction orders.

It is worth pausing to contemplate just how staggering are Figures 7. Roughly half of all these cases – essentially child arrangements cases – involve allegations of domestic violence.

Is this really credible?

Figure 7a Click to enlarge

Figure 7b Click to enlarge

NB: the blip in Figure 7b at 2014 Q3 is attributed in the source reference to an audit by HMCTS of all open private law cases in that quarter.

The 2015 parliamentary Justice Select Committee inquiry into the impact of changes to civil legal aid under LASPO made the following remarkable observation, adding emphasis by using bold text,

“We note with concern the evidence from the Rights of Women survey suggesting 39% of women who were victims of domestic violence had none of the forms of evidence required to qualify for legal aid. Any failure to ensure that victims of domestic violence can access legal aid means the Government is not achieving its declared objectives.”

But if we add a further 39% to Figures 7 we virtually achieve 100% – so is every women in a child arrangement dispute a victim of domestic violence? Apparently so, if Rights of Women are to be believed – and believe them the Justice Select Committee certainly does.

To facilitate the Committee’s joint objective with Rights of Women, and, of course, Women’s Aid from whom they also took evidence, the Committee wrote,

“We welcome the Ministry of Justice’s commitment to keeping the types of evidence required to qualify for the domestic violence gateway under review and recommend the introduction of an additional ‘catch-all’ clause giving the Legal Aid Agency discretion to grant legal aid to a victim of domestic violence who does not fit within the current criteria.”

Got that? Allow me to paraphrase: never mind the charade about ‘evidence’, just give legal aid to any women who claims DV.

7. False Allegations Before LASPO?

Let us pause our examination of the effects of LASPO for a moment to consider more closely what Figures 7 imply. Contrast Figures 7 with Figure 4, the incidence of DV in the population as a whole. In recent years some 6% of women report being a victim of DV in the preceding year. This contrasts with around 50% claiming DV during family court child hearings. The former figure is ‘per year’. Before April 2016 the DV gateway explicitly required that DV incidents must be within two years of the date of application to be considered. (Whilst this was extended to 5 years in April 2016, all but the last quarter or two of data quoted here relates to the earlier period). The percentage of women experiencing DV over a two year period will not be double 6% because some incidents will involve the same victim. However it will not exceed 12%.

If the couples meeting in court over a child arrangement dispute were a random sample of the population it would follow that there is an unexplained gap between the 12% or fewer women who would be expected to be victims of DV, and the roughly 50% who claim to be so in the family courts. Is there not a prima facie case for suspicion here?

The “if” in the above observation requires amplification. The excess of DV allegations in the family courts over that expected based on the population as a whole would potentially be explicable, without false allegations, if DV were the cause of a large proportion (about half) of divorces and hence child arrangement disputes. But is this so?

MoJ data indicates that “behaviour” is the most common cited reason for divorce. However, one cannot equate “behaviour” with domestic violence. In fact, in view of the nature of our suspicion, one cannot rely upon data obtained via the courts or their associated functionaries in respect of this issue. However, there are many informal sources which provide a perspective on the commonest reasons for divorce. Although by no means scientific, various ad hoc polls of the public can be found with a little Googling, for example here and here and here and here. Abuse does get the odd mention, but generally only in articles emanating from the legal profession – who are probably guided by the very statistics we are questioning. The public polls most often do not mention partner abuse in their top ten or top twenty reasons for divorce. This is by no means definitive, of course, but it does cast further doubt on whether it is really true that ~50% of child arrangement cases involve genuine DV.

And this aspersion refers to the situation before LASPO as much as after.

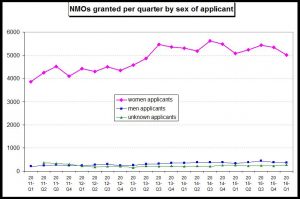

8. NMOs by Sex of Applicant

So far it has been tacitly assumed that allegations of DV, and hence NMOs, are overwhelmingly dominated by female accusers and alleged male perpetrators. This is true, as illustrated by Figure 8 which shows how NMOs granted split by sex. Men constitute only 5% – 7% of applicants. [I have not seen a breakdown by sex of alleged abuser. However it is likely that same-sex cases account for only a very small proportion of the total, recalling that the data relate predominantly to child arrangement cases].

Figure 8 (Data obtained from MOJ via FOI enquiry by FNF) Click to enlarge

9. What Path Through the Gateway?

In Section 2 the many ways were listed by which ‘evidence’ sufficient to be granted legal aid may be acquired via an allegation of DV. Even the least critical person will note that many of these options do not constitute evidence in any meaningful sense. For example, “evidence from a domestic violence support organisation of a stay in a refuge”. It is well known that the refuge charities will automatically believe a women alleging abuse. In the context of providing refuge facilities this may be a perfectly reasonable policy. However, automatic acceptance of a woman’s allegation hardly constitutes validation.

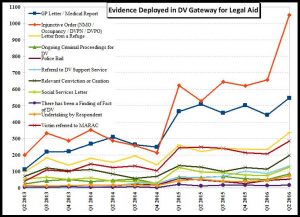

Another of the paths through the gateway listed in Section 2 is the granting of a protective injunction. It was noted that an application for a protective injunction following from an allegation of domestic violence will be funded by legal aid, without means testing and without any need for evidence. Upon such an injunction being granted, the injunction itself then provides ‘evidence’ for the granting of further legal aid to the alleged victim in the private family law proceedings, e.g., over child arrangements. This remarkable facility is rather like being able to pick yourself up by your own bootlaces. So how frequently is this particular path through the gateway used? The answer is: more than any other route.

Figure 9 shows how many legal aid awards were granted by evidence offered. Note that more than one item of evidence might be offered, so the sum of the curves in Figure 9 will slightly over-estimate the total number of legal aid awards. The injunction order route (dominated by NMOs) is the most frequently deployed route – and this is increasing steeply in frequency now. This is hardly surprising in view of how readily it accommodates the false accuser.

Table 1 gives the data for 2016 Q2 as the percentage for each path through the gateway. Note how small a percentage is accounted for by the more robust evidence, e.g., ongoing criminal proceedings for DV, or a prior conviction for DV, or a “finding of fact” of DV. The latter, which is the only pathway which actually examines the accusation itself, accounts for just 0.6% of cases.

It really is hard to believe. Or, rather, it isn’t. Not anymore.

Figure 9 (Data obtained from MOJ via FOI enquiry by FNF) Click to enlarge

Table 1: Different paths through the DV gateway

| DV Gateway ‘Evidence’ for Legal Aid | Percentage of cases deploying this type of evidence (2016 Q2 data) |

| Evidence of financial abuse | 0.1% |

| GP Letter / Medical Report | 18.8% |

| Injunctive Order (NMO / Occupancy Order, etc) | 36.1% |

| Letter from a Refuge | 11.5% |

| Ongoing Criminal Proceedings for DV | 3.0% |

| Police Bail | 1.9% |

| Referral to DV Support Service | 4.6% |

| Relevant Conviction or Caution | 6.8% |

| Social Services Letter | 4.3% |

| There has been a Finding of Fact of DV | 0.6% |

| Undertaking by Respondent | 2.5% |

| Victim referred to MARAC* | 9.8% |

*multi-agency risk assessment conference

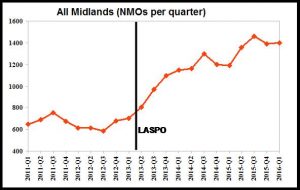

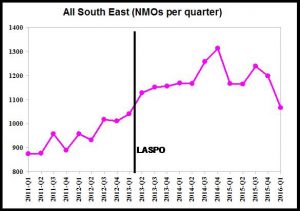

10. Numbers of NMOs by Region

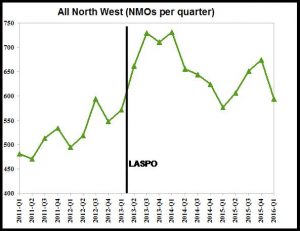

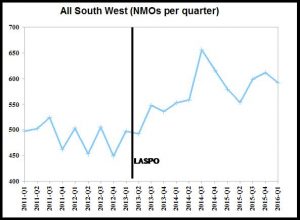

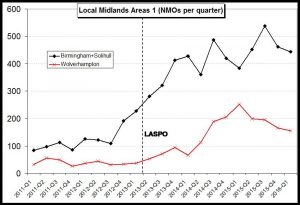

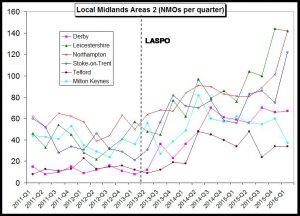

In Section 5 it was noted that, across England and Wales as a whole, the volume of NMOs has increased by ~20% post-LASPO (Figures 5 and 6). But this is not uniform across the country. Wales, London and the North-East show no overall increase in NMOs. In contrast, the Midlands, the North-West, the South-East and the South-West all show significant increases (where ‘significant’ means at the 99.9% confidence level). The increases are shown in Table 2 and graphically in Figures 10 to 13.

By far the greatest increase in NMOs is found in the Midlands region.

Even in London and the North-East, individual Designated Family Justice Areas (DFJA) can be found which show significant increases in numbers of NMOs. In fact there are dozens of DFJAs around the country which show large percentage increases in NMOs after LASPO. An exhaustive presentation of the data would overburden this article, however a few examples of local DFJAs are given in Section 11.

Table 2: Changes in Quarterly Numbers of NMOs Between Periods (a) and (b) by Major Region [Period (a) is the 9 quarters prior to LASPO; Period (b) is the 12 quarters after LASPO].

| Region | Mean in Period (a) | Mean in Period (b) | Percentage Increase |

| Midlands | 663 | 1206 | 82% |

| North West | 525 | 655 | 25% |

| South East | 951 | 1181 | 24% |

| South West | 488 | 574 | 18% |

| England & Wales | 4,884 | 5859 | 20% |

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

11. NMOs Issued by specific Designated Family Justice Areas (DFJA)

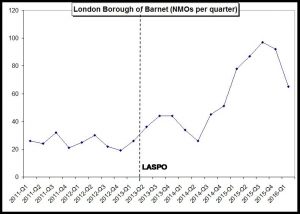

Dozens of individual courts (DFJAs) have issued substantially more NMOs since LASPO. Here I give just a few examples. Figures 14 and 15 are the chief culprits in the Midlands, whilst Figure 16 is the worst in London, namely Barnet. The increases are given in numerical form in Table 3.

Table 3: Changes in Quarterly Numbers of NMOs Between Periods (a) and (b) for Example DFJAs in the Midlands Region or London [Period (a) is the 9 quarters prior to LASPO; Period (b) is the 12 quarters after LASPO].

| Region | Mean in Period (a) | Mean in Period (b) | Percentage Increase |

| Telford | 13.8 | 30.4 | 121% |

| Stoke On Trent | 37.0 | 72.4 | 96% |

| Birmingham+Solihull | 128.0 | 416 | 225% |

| Derby | 11.6 | 50.3 | 336% |

| Leicestershire | 39.8 | 88.3 | 122% |

| Northampton | 54.9 | 86.8 | 58% |

| Wolverhampton | 38.2 | 147.0 | 284% |

| Milton Keynes | 38.4 | 53.3 | 39% |

| Barnet | 25.0 | 58.3 | 133% |

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

12. Abusers Cross-Examining Victims

Taking into account all the above information, what is a typical situation in the family courts? A mother makes an accusation of domestic violence and receives legal aid, whilst the man she has accused gets no legal aid and, being non too rich, is obliged to manage his own defence. Enter the lurid headlines such as Revealed: how family courts allow abusers to torment their victims. We read that “violent and abusive men are being allowed to confront and cross-examine their former partners in secretive court hearings that fail to protect women who are victims of abuse“.

Well, yes, quite possibly – in some cases. But the majority of these men cannot legally be called perpetrators of domestic violence, only alleged perpetrators, and the loaded terms “victim” and “survivor” are equally unproved in most cases (as is clear from Table 1). So these men, having done nothing wrong in many cases, and having been denied the legal aid that their accuser has received, are now being criticised for attempting their own defence.

The ever-so-chivalrous judiciary has wasted no time in responding to this plea (command?) from women’s groups to stop women accusers being cross-examined by the accused. This matter has been discussed in a report to the President of the Family Division by the Hon. Mr. Justice Cobb (the main purpose of which is a proposed revision to Practice Direction 12J FPR 2010 – Child Arrangement and Contact Orders: Domestic Violence and Harm – which does not concern us here but relates to the subject of my previous post 332 Child Homicides). In undertaking this review, Mr Justice Cobb consulted Women’s Aid, the Rights of Women, Professor Rosemary Hunter (Queen Mary University of London), Prof Marianne Hester (University of Bristol) and Dr Gillian Macdonald (University of Bath). Professor Hunter’s major area of research interest is in feminist legal scholarship. Professor Hester is chair of Gender, Violence and International Policy at Bristol University, whilst Dr Macdonald’s sympathies can be judged from the title of this conference presentation, “Domestic Violence and Private Family Court Proceedings: promoting child welfare or promoting contact?“. No bias there then.

In his review, and in the context of cross-examinations, Mr Justice Cobb writes that, “Women’s Aid require the Family Court judiciary to play its part in managing and averting these potentially abusive situations in the courtroom“. Require? An interesting, and rather revealing, choice of word.

Mr Justice Cobb advises the following course,

“The judge or lay justices must not permit an unrepresented alleged abuser to cross-examine or otherwise directly question the alleged victim…..The judge or lay justices may conduct the questioning on behalf of the other party in these circumstances.”

One wonders if barristers would be happy to be made redundant in favour of the judge putting their questions to witnesses instead. I suspect not. And whatever objections they would raise to such a course must surely apply here also.

The bottom line is that grossly inequitable legal aid arrangements under LASPO have led to a situation which even the intellectually challenged could easily have anticipated. What is proposed is another fudge to prop up the previous mess.

Family Court judges do know the current situation is problematic. But the LAA is intransigent. A graphic illustration of this is provided by a case in which a man was accused, within the family court, of raping his wife. She had legal aid, he did not. The family court judge was concerned for three reasons: (i) that such a serious charge was effectively being dealt with in the family court at all, (ii) that the man had no representation to defend himself against such a serious charge, and, (iii) that the court would be obliged to permit a man accused of rape to cross-examine his alleged victim. Consequently the judge wrote to the LAA seeking legal aid for the man in this particular circumstance. They refused.

13. Conclusions

LASPO withdrew legal aid from private family law cases, unless allegations such as domestic violence were raised. The ‘evidence’ required to support obtaining legal aid via a DV accusation is defined by a gateway as wide as the Grand Canyon. Since LASPO the number of grants of legal aid obtained via the DV gateway has been climbing steadily, despite falling rates of DV in the general public. Who would have guessed?

The most popular route to obtaining legal aid in such cases is via a non-molestation order (NMO). The process is so accommodating that it might as well have a sign attached “false accusers welcome”. An application for an NMO will be funded by legal aid, without means testing and without any need for evidence. Upon an NMO being granted, the NMO itself then provides ‘evidence’ for the granting of further legal aid in the private family law proceedings, e.g., over child arrangements. One can readily understand the temptation a woman would feel to avail herself of this opportunity, especially when her predominant emotional state is to punish, or merely outdo, her ex.

LASPO has led to a substantial increase in the volume of NMOs which is evident in the overall statistics for the Midlands, the North-West of England, the South-West of England and the South-East of England. Over England and Wales as a whole, the number of NMOs has increased by 20% post-LASPO and this change occurs unambiguously at the time of LASPO. By far the greatest increase in volume of NMOs post-LASPO is found in the Midlands (82%).

Apparently we are expected to believe that about half of all child arrangement cases in private family law involve a father who is guilty of domestic abuse. Has no one, out of the many thousands who work in this area, thought to question this staggering statistic? We have all been groomed to believe such a thing by decades of media messages, promulgated by committed feminists, that men are dangerous abusers. But the bald statistics presented herein paint a different picture. The data strongly suggest that most DV allegations in private family law are false.