My thanks to Oxford Men’s Group for hosting and organising this event, and for giving me a platform for my hobbyhorse: the true history of universal suffrage in the UK. The video of the talk on YouTube is here. Some platforms have a synch problem with this, in which case try the BitChute version here.

The transcript of the talk is below, followed by full references to the quotations used.

At just a few minutes over the hour, the talk is more approachable than my 25-part epic. I also think I’ve consolidated the argument further now, with a number of key quotations added.

*************

The Real History of the Representation of the People

A talk for the Oxford Men’s Group, Oxford Town Hall, 1 November 2018

I am delighted to have been given the opportunity to speak on a subject which has become something of a hobbyhorse of mine: the history of universal suffrage in the UK. One might equally call it, the history of democracy in the UK, and that will give you an immediate hint as to the tenor of my talk. Although the subject is both historical and political, I must disabuse you of any presumption that I necessarily have a broader competence in matters historical or political. Nevertheless, I will be happy to take questions at the end, at which time I might display some political prowess if only in my ability to sidestep them completely.

I am particularly happy to address the subject of the history of universal suffrage because, of course, this year we celebrate the centenary of the Representation of the People Act 1918 and because, in my opinion, the latter stages of that history have become mired in myth. This is a pity because the truth is more interesting and more uplifting.

So – the 1918 Representation of the People Act. This is the Act which gave the Parliamentary vote to the majority of women for the first time in the UK, and that is what one generally hears being celebrated in this centenary year. Well, the acquisition of the Parliamentary vote by women is a perfectly valid thing to celebrate. But it’s not the only aspect of that Act to celebrate – or even the most significant aspect. The 1918 Act should be celebrated for something more fundamental. It should be celebrated for the triumph of democracy.

It has been forgotten now that until 1918, democracy – in the sense of one-adult-one-vote – had been widely regarded as a dangerously radical, even subversive, idea.

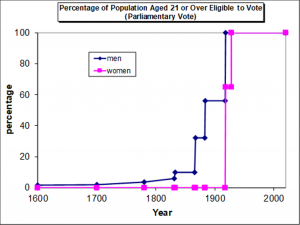

I have not conducted a poll but I feel fairly sure that to most people the phrase “universal suffrage” would be taken to mean “votes for women”. Yet when the suffragette campaign was at its height, only 56% of men over 21 had the vote, and just a few years before the Victorian era, only about 4% of adult men had the Parliamentary vote. Between 1832 and 1928 a political process took place which, in stages, gave the Parliamentary vote at 21 to all men and all women. This is universal suffrage.

The history of universal suffrage is the history of the working class struggle, not just votes for women. Men, too, had to fight for the vote – sometimes literally.

My thesis will be that the processes at work in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries addressed the manhood claim to suffrage and the women’s claim largely in parallel, in symbiosis not in conflict. To discuss women’s demand for the vote in isolation from men’s parallel demand is to understand neither. And the role played by World War 1 in the final outcome has not been properly appreciated.

The modern myth that female suffrage consisted simply of heroic suffragettes battling – to quote Lang (Ref.[1]) – a chauvinistic male establishment consisting only of blinkered politicians, burly policemen and brutal prison warders, does not do justice to the full story. Indeed, that version of events is divisive, whereas the true history of universal suffrage shows how the causes of the two sexes were inextricably connected. The true story unites rather than divides. I commend it to your attention.

To start the story in the suffragette era would be to open the book at the last chapter. Even to start the story in 1832 with the First Great Reform Act would be to open the book in the middle. Whilst there had been no progress in extending the Parliamentary franchise before that date, it was not for lack of trying. In a sense, the progress made from 1832 might be seen as the denouement of previous centuries of struggle, albeit ostensibly fruitless struggle. It is very important to recall, if only briefly, some key events over those preceding centuries in order that nineteenth century events take on their proper perspective.

The suffragettes’ imprisonment and hunger strikes are well known. The huge numbers of men imprisoned, transported to penal colonies, killed in battles or executed in pursuit of their parallel cause in earlier centuries tends to be forgotten. Let’s take a very brief look at that deeper history.

Life in post-conquest England was dominated by agriculture, controlled by the Manor. The feudal system reigned. Control of the land was presided over by the Lord of the Manor. 86% of the people, the villeins, cottagers and serfs, were not free. They were chattels of the Lord, legally bound to the Manor, they could not leave without permission. They could not even marry without permission – and had to pay to do so. Poverty was hereditary and inescapable. Villeins were required to provide labour on the Lord’s own land, the Home Farm, without pay. The majority of people were little better than slaves.

The chief yoke under which the villeins, cottagers and serfs toiled was being unfree. A struggle for emancipation was inevitable. The demand was to be freed from the degrading personal aspects of serfdom and the right to recognition as a full human being, not a chattel.

The matter was brought to a head in the 14th century by the English kings’ insistence on pursuing a cripplingly expensive war with France – the so-called 100 years war – funding the same with successive waves of taxation. At this point the Peasants truly did become Revolting. Enter Wat Tyler, John Ball and a 60,000 strong peasant army. But their grievance was principally taxation, though they did also call for the abolition of serfdom. They had little political acumen and even less discipline. The revolt was dissipated – in both senses – and the leaders put to death in 1381.

In contrast, Jack Cade’s Kentish rebellion in the 15th century was principally about the corruption and abuse of power by noblemen and others of the King’s advisors. This was beginning to become political and involved some noblemen as well as peasantry. This rebellion’s 12-point Proclamation of Grievances or The Complaint of the Poor Commons of Kent started with a reminder to the King that he was not above the Law. Initially victorious against Henry VI’s troops at Sevenoaks, Cade and his followers entered London, but Cade was no more successful than Wat Tyler and Co at keeping any discipline. The rebellion ended in a battle in Southwark in which 240 men were killed, mostly rebels. Cade and the other leaders were later treacherously executed after having first been pardoned.

This Kentish rebellion subsequently inspired copy-cat rebellions in other counties, these becoming more radical and aggressive in their demands for reform.

The 16th century saw Robert Kett lead another rebellion, this time in Norfolk, with enormous loss of life. The rebellion was caused by the enclosures which robbed the peasantry of their common grazing land. With the help of educated men, the peasants were able to draw up lists of grievances to be addressed. The tone was now both religious and political. This peasant uprising was initially met with a force of 1400 soldiers, but the soldiers were defeated. Then the Earl of Warwick threw 12,000 English troops plus 1,200 German mercenaries at them and the peasants were slaughtered at the battle of Dussindale in 1549. Some 3000 peasants were killed. At least fifty more were subsequently executed for treason.

Another century, another bid for emancipation: in the 17th century, enter The Levellers. Perhaps emboldened by their defeat of the Monarchy, some members of Cromwell’s parliamentary army had the temerity to support calls for universal (male) suffrage. What cheek – in 1647! The Levellers were 271 years ahead of their time. Their significance lay not in their success – they had none – but in their continuance of the theme of increasing political awareness. To quote Harrison (Ref.[2]),

“They wanted an effective say in the making of decisions which closely affected them, and they saw that they would never achieve that without political power. Hence their concern for democratic government at the local and national levels.”

Obviously radical nutjobs who badly needed suppressing.

And such views would indeed be suppressed for a long time, but not forever. During the 18th century, technological and economic conditions changed considerably and the industrial revolution reached full steam. Arguably as a result, in the early 19th century there was a rash of political unrest from the masses.

In 1810-1816 there were the Luddites, famous for their ‘unprogressive’ attitude towards factory machinery, though they were actually protesting for better pay – or any pay at all – rather than against the machines. The machine smashing was simply their form of protest. Shooting the vandals proved efficacious. The army was used. Lord Byron – he of the mad, bad and dangerous to know appellation – spoke in defence of the Luddites in the House of Lords, comparing their plight unfavourably with the poorest wretches in his beloved Turkey.

The rural equivalent of the Luddites were the followers of ‘Captain Swing’ who took to smashing threshing machines. The ‘Swing’ riots began following some terrible treatment of those on poor relief, including the harnessing of men and women to carts, and the discovery of harvest labourers starved to death in a ditch. Nearly 2000 Swing rioters were brought to trial in 1830/31. 252 were sentenced to death, 481 were deported to penal colonies in Australia, and 644 were imprisoned. This draconian treatment was meted out despite no one, other than one rioter, having been killed in the riots.

In 1819 there was the Peterloo massacre in Manchester. Some 60,000 men and women had gathered to hear a speech as the culmination of a reformist campaign whose purpose was the reform of parliamentary representation. The meeting in St Peter’s Square was entirely peaceable – until the yeomanry’s attempt to arrest the speaker led to them charging the crowd with sabres swinging. There were 654 recorded casualties, and 18 people were killed. Unlike previous violent unrest, a substantial proportion – about a quarter – were women.

Then there were the famous Tolpuddle martyrs of 1834. Insignificant in number, just six, but highly significant in regard to the ever growing political focus of the popular unrest. They were transported for the crime of forming a trade union. They called for universal male suffrage. Their bible was Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, a work which was then being re-published and popularised by the radical journalist Richard Carlile.

Recall that Paine’s Rights of Man was inspired by the French Revolution. Paine argued that revolution is morally justified when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. Remember that when we get to the Reform Acts and their motivation.

And finally, of course, there were the Chartists. Their six-point Charter was entirely about political representation of the common people in Parliament. The main policy of the Chartists was to achieve universal male suffrage. In their early days, they were so radical as to propose universal suffrage for both sexes, but quickly retrenched on the grounds that votes for women was rather too great a stretch. In the end, of course, universal male suffrage was barely achieved much before that of women, as we shall see. And the Chartists themselves, like the Peterloo crowd, were of both sexes.

The depression of 1841–1842 led to a wave of strikes in which Chartist activists were in the forefront, and demands for the Charter were included alongside economic demands. Hundreds of Chartists were arrested and either imprisoned or transported to Australia.

The Chartist movement organised several huge petitions in favour of their People’s Charter, each with several millions of signatures. Their Charter was eventually debated in Parliament in 1848, but rejected.

All this was the background to the Reform Acts of the nineteenth century – namely, centuries of popular unrest and eminently justified discontent – and it is to these Reform Acts I now turn.

The Great Reform Act of 1832 was not so great as regards the working man – and especially not for women. Before 1832 the disfranchisement of women had been by custom rather than by statute. To quote House of Commons Research Paper 13/14 (Ref.[3]), prior to 1832 “it is impossible to conclude that women never voted”. To quote Millicent Fawcett (Ref.[4]), “The claim that in ancient times women did exercise the franchise, whether capable of being established or not, certainly does not deserve to be dismissed as in itself absurd and incredible”. I agree.

Immediately prior to the Great Reform Act about 4% of men had the Parliamentary vote at age 21. The Act increased this initially to about 8% of men.

But the intention of the 1832 Act was not primarily to extend the franchise. Its purpose was to correct flagrant partisanship inherent in the system for electing Members of Parliament. In the hundred years before the Great Reform Act, one-quarter of all the constituencies of England and Wales had had either no election or just one election. In those days, many elections were uncontested. The ruling classes effectively decided amongst themselves who would take a seat. The system was completely rotten.

The motivations of MPs for bringing the 1832 Act were complicated, to put it mildly – but democracy was certainly not one of them. The British establishment had never recovered from the shock of the French revolution – and Thomas Paine and Co hadn’t helped. The fear of contagion spreading to England remained even at this period. The frequent working-class riots and increasingly political working class agitation added to the concern. This was, no doubt, why the Swing rioters were punished so harshly. Historians can argue amongst themselves whether Britain really was in danger of revolution prior to the Great Reform Act. But enough of the people that mattered in 1832 believed it – so the Act was passed.

The working class were not fooled for long regarding the failure of the Great Reform Act to address their concerns. This, together with the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, which introduced the deliberately hateful Workhouses, is what prompted the popular Chartist movement. Whilst that movement ostensibly achieved nothing, the unrest caused by this and other movements of the era inevitably weighed upon the minds of those in power. Moreover, the Victorians, for all their faults, did at least believe in rewarding contribution to the national good. There was a growing recognition by the political elite that the national wealth was increasingly dependent upon a new type of technological citizen, both of middle class and proletarian varieties.

The second Reform Act of 1867 was a response to two things: an increasingly vociferous lobby arguing for liberal principles and also a response to the political rise of the nouveau riche mill owners. The latter brought with it the recognition of what became known as the ‘labour aristocracy’. These were the skilled men that the country increasingly depended upon. Not just anyone could maintain the steam engine which drove a factory, still fewer could make one in the first place. The old emphasis on maintaining entrenched privilege was beginning to give way to a more egalitarian idea that, whilst the vote was not seen as a right, it was something that could be earned.

Immediately prior to the 1867 Act, around 12% of adult men had the vote and the Act increased this to about 32% of men at age 21.

What certainly did not underlie the second Reform Act is sympathy for the idea of democracy. In the mid-Victorian period, democracy was still a dangerously radical notion. A quote of Disraeli’s from his speech proposing the 1867 Bill (Ref.[5]) makes the establishment distain for democracy abundantly clear, “we do not live – and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live – under a democracy. The propositions which I am going to make tonight certainly have no tendency in that direction”.

Can you imagine an MP today proposing a Bill with an assurance that it would be absolutely uncontaminated by anything so vile as democracy? And Disraeli was surely being disingenuous. Had the thought never entered his head that his 1867 proposals were indeed a step along the road to democracy, he would not have felt it necessary to refute it.

Nor had democracy stopped being a dirty word by the third Reform Act. Even in 1884, leading politicians still regarded democracy as a dangerous tendency. The third Reform Act -sometimes referred to as the “County Franchise Bill” – was essentially more of the same. More working class men got the vote, but the franchise was still household-based and excluded nearly half of men.

After the 1884 Act, 56% of men had the Parliamentary vote at age 21, but still no women. This was to remain the position on the franchise until 1918. For 34 years there was no further progress. The reason why is the focus of the rest of this talk.

After the third Reform Act we enter the period of energetic women’s suffrage activities. The period between 1884 and 1918 is the period on which I want now to concentrate. But it would be a great mistake to imagine that lobbying on behalf of the women’s cause started only in this period, merely because it had not yet born fruit. Recall that agitation for male suffrage had been intermittently pursued for centuries before the first progress was made in 1832.

Jeremy Bentham had argued for female suffrage as early as 1817, when only 4% of adult men had the Parliamentary vote. The MP Henry Hunt was another early advocate for the women’s vote. After the enactment of the 1832 Great Reform Act, Hunt argued that any woman who was single, a taxpayer and met the same property criteria applied to men should also be allowed to vote. John Stuart Mill was elected MP for the City of Westminster in 1865 on a platform including votes for women. While a member of Parliament, Mill presented a petition for woman’s suffrage in 1866. He proposed an amendment to the second Reform Bill in 1867 to include female suffrage on the same terms as male suffrage. Though it was defeated, by 196 votes to 73, it did demonstrate some significant support for female enfranchisement even when the proportion of men with the vote was still only about 12%.

The naïve idea which informs the popular narrative today, namely that men’s enfranchisement was established long before – perhaps centuries before – women’s enfranchisement was even dreamed of – is complete fiction. After all, Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man completed publication in 1792, the same year that Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. The progress towards universal suffrage of both men and women was not two separate processes but one single process. The process in question was the working class struggle.

Yes, even the enfranchisement of upper crust women was entangled in the working class struggle.

At this point we come to the most interesting and most misunderstood part of the history. This final phase of the history of universal suffrage is the part which demonstrates most clearly how the fates of men and women are intertwined. What I hope to convince you of is this: the reason why the enfranchisement of women was delayed rather longer than that of men was not primarily because of lack of male politicians’ support for female suffrage. Rather, it was because of a Party Political issue relating to the electoral impact of enfranchising women at a time when working men were not yet fully enfranchised. This is an issue that seems never to have been clearly enunciated and which I refer to as the Big Snag.

My contention is that the barrier to giving women the vote – any women at all – was the incomplete enfranchisement of working class men.

My contention is that the enfranchisement of working class men was viewed far more negatively by the establishment – and hence was far more difficult to accomplish – than the enfranchisement of women per se. But – and this is what has not been understood – the former was a barrier to the latter.

But I get ahead of myself. Let’s take this at a more measured pace.

Firstly, what support was there amongst MPs for the enfranchisement of women, and at what date?

The same Benjamin Disraeli who, 19 years later was still so very disparaging about democracy – by which he essentially meant the working class male vote – nevertheless made clear as early as 1848, and several times thereafter, that he was in favour of female suffrage.

I need not laboriously quote the opinions of individual MPs. Millicent Fawcett stated simply in 1912, “There has been a majority in the House of Commons in favour of women’s suffrage since 1886” (Ref.[6]).

Emmeline Pankhurst notes the same herself in her autobiography, “…in 1884, when the County Franchise Bill came before the country, we had an actual majority in favour of suffrage in the House of Commons” (Ref.[7]).

The Parliament elected in January 1906 contained an overwhelming Liberal majority; it also contained more than 400 members, belonging to all parties, who were pledged to the principle of women’s suffrage. This was a substantial majority of MPs. In 1908, Asquith, now Prime Minister “admitted that about two-thirds of his Cabinet and a majority of his party were favourable to women’s suffrage”.

I trust I have laboured this point enough. There had been a majority of MPs in favour of female suffrage, in some form, since at least 1884. The idea that the vote for women was blocked by a chauvinistic male political hegemony is false.

Let me drive the issue home further with this fact: between 1870 and 1918, a staggering sequence Bills and Resolutions relating to women’s suffrage were put before Parliament. Debates took place in 1870 (twice), 1871, 1872, 1873, 1875, 1876, 1877, 1878, 1879, 1883, 1884, 1886, 1890, 1892, 1897, 1904, 1905, 1908 (twice), 1910, 1911, 1912 (twice), 1913, 1914.

Altogether, ignoring Resolutions, some 17 such Bills were introduced into the House of Commons (and one in the House of Lords), and 8 passed their second reading, i.e., in the years 1870, 1886, 1897, 1908, 1909, 1910, 1911, 1912.

The sheer number of Bills speaks of the degree of support in Parliament – otherwise MPs would surely have given up. But, given the apparent support, why did Bill after Bill fail to gain assent? If there was so much support for women’s suffrage, why was it so long in coming to fruition? Why did women have to wait another 48 years after the first attempt at a Bill before any women got the vote?

The prevailing popular narrative today does not address this paradox because it does not recognise there is one. The approved mythology refuses to acknowledge that there was a majority of male politicians in support of female suffrage from at least 1884, if not earlier. This, you see, would conflict with the appealingly simple story of a belligerent male hegemony withholding the vote from women out of shear misogyny.

There was, however, a male hegemony in operation. But its target was not women. Its target was the working class.

Why? The answer in a word is “fear”.

John Stuart Mill asked (Ref.[8]), “Why is nearly the whole educated class united in uncompromising hostility to a purely democratic suffrage?……It is because it would make the working class the sole power, because in every constituency the votes of that class would swamp and politically annihilate all other members of the community taken together.”

Charles Bradlaugh, the radial atheist and universalist MP for Northampton, observed in 1884,

“This political death (i.e., electoral annihilation), which occurring to any body of citizens is a most grievous injury to the state, has terror for the upper 10,000, notwithstanding which, they appear to deem it the rightful fate of the lower 10,000,000.” (Ref.[9])

And Bradlaugh again, Ref.[10],

“There are many even in pure Belgravia who would willingly accord to the working man some share in the government, but who fear that if the right of suffrage be attained by the people, it will be used to destroy politically the whole of those in whom political power is at present vested…..they declare their conviction that in a House of Commons returned by universal suffrage, there would be no justice done to the rights of property.”

The real reason that the political class did not want to see the working class enfranchised was fear – fear that power in the hands of the working class would result in the elimination of ancient property rights and fear of retribution for centuries of mistreatment. It was no secret. Here is what Millicent Fawcett (Ref.[11]) wrote of the situation in 1865,

“Each party brought forward Reform Bills, but neither party really wished to enfranchise the working classes……Besides the extra trouble and expense involved (in increasing the electorate), there was in 1865 another deterrent – terror. Those who held power feared the working classes. Working men were supposed to be the enemies of property, and working men were in an enormous numerical majority over all other classes combined.” She continued, “You must not have the vote because there are so many of you” was a much more effective argument when used against working men than when used against women; because the working classes are fifteen or sixteen times more numerous than all the other classes combined, whereas women are only slightly in excess of men.”

Fawcett correctly recognised that the issue of the franchise was an issue of electoral arithmetic, especially as regards the working class.

So, we have established two things: (i) there had been a majority of MPs in support for women’s suffrage for some considerable time, and, (ii) that there was fear regarding extending the vote to working class men. The final piece in the jigsaw is to understand why the latter was the barrier to the former. My answer is that there was simply no party-political route to passing a Bill which would give the vote to women without first having enfranchised all working class men. This was the Big Snag and it worked like this.

Consider any attempt to give the vote to some women without extending the franchise to more men. Which women could possibly receive the vote? Well, at most, only those women who ‘matched the enfranchised men’, that is, the upper half of society. The many attempts to enfranchise some women prior to 1918 had all been constrained by this consideration, and, in practice, tended to offer the vote to an even more restricted class of women – “the most respectable” women, you might say.

But this meant – or was presumed to mean – predominantly women who would vote Conservative. By giving the vote to a few million new Tory voters, the Liberal Party, and later also the Labour Party, would, to put it bluntly, be shafted in the elections. So the very Parties which were sympathetic to votes for women, in principle, got cold feet when it came to the practice. And Asquith – who was Prime Minister throughout most of the suffragette period – was Liberal, as was most of his Cabinet. He was well placed to scupper private members Bills which he perceived as an electoral threat to the Liberals.

The Conservatives were not, in general, ideologically in favour of women’s suffrage – though it is noteworthy that quite a few individual Tories were supportive. However, there was a threat that the Conservatives might support limited suffrage for a few ‘respectable’ women because of the electoral advantage it was presumed it would give them. The dominance of the Liberal Government after 1905 would ensure this threat to their election chances would not materialise, despite a majority of their Liberal MPs supporting female enfranchisement in principle. In short, the Liberal Government under Asquith would repeatedly frustrate their own Liberal members ideological zeal for female suffrage on the altar of safeguarding the Liberal electoral position.

Of course, this problem could have been overcome by also granting the vote to working class women. But this could obviously not be done unless working class men were also given the vote. For this reason it was a party political impossibility to give the vote to women – any women at all – until the vote had first been extended to all working class men. This was the Big Snag.

In short, the only viable route to female enfranchisement of any sort lay through universal adult suffrage. The barrier to female enfranchisement was the class issue of enfranchisement of the working class, not primarily an issue of sex. If you take away just one message from this talk, take that.

[In passing I refer you to the book by American academic Dawn Lagan Teele, “Forging the Franchise: The Political Origins of the Women’s Vote”, Ref.[12], published in October, which strongly consolidates the argument for the significance of electoral arithmetic in frustrating the passage of female suffrage Bills prior to 1918].

From 1870 to 1914, Bill after Bill including some measure of female suffrage was proposed but none could ever satisfy all Parties. They prioritised protecting their electoral chances. Millicent Fawcett was well aware of the fact, as was Emmeline Pankhurst, the latter observing, “the Conservatives insisted on a moderate Bill, whilst the Liberals were concerned lest the terms of the Bill should add to the power of the propertied classes”, Ref.[13].

The prominence of the suffragettes in the public imagination has led to an incorrect understanding of this period. The suffragettes – more properly called the WSPU, the Women’s Social and Political Union, headed by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst – were not the only campaigners for women’s suffrage, nor the largest, nor the most important. More important was the quieter politicking driven by many other suffragist organisations, of which Millicent Fawcett’s NUWSS, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, was the largest and best known. But there were not simply two women’s suffrage groups. By the 1890s there were seventeen individual groups advocating for women’s suffrage in the UK, and more would be formed over the next twenty years, though some would later merge.

There is another manner in which the flamboyant suffragette activity has eclipsed key parts of the history. It has given the impression that there was no campaigning in this period on behalf of the disenfranchised working class men. This is completely untrue. By this time, working men increasingly had a mechanism for political representation through the trades unions, the Labour Party and the Independent Labour Party. These were all pursuing extension of the franchise to the working class, and working men were their first priority.

In the decades before World War 1 there were two different fault lines which fractured the suffragist movement: the first was sex, and the second was class. What confused the issue was that these two factors were correlated. The men’s cause was irreducibly also a class cause because it was specifically working class men who were not fully enfranchised. But, until very late in the history, the women’s cause also presented itself to many as a class cause, because its leaders were middle class and most of the proposed Bills attempted to enfranchise only a small proportion of the “more respectable” women.

There was therefore antagonism between the two sides – which appeared to be sex based, but was, in truth, class based. What is staringly obvious today, namely that unification of the two sides could have been achieved through universalism – the enfranchisement of all regardless of sex or class – was not so easily seen then – especially when trying to negotiate the thickets of Party Political electoral interests.

There are two key features of the history in the ten years before the 1918 Act. Firstly, there was the growing together of the men’s and women’s causes under the policy of universalism, and secondly, there was World War 1. But even in, say, 1908, the main thrust of the women’s movement was still a long way from universalism.

In the latter respect, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst’s WSPU, the suffragettes, were the chief culprit. In seeking the vote for women ‘on equal terms with men’ or for ‘tax paying women’ only, the WSPU had little to offer the working class – of either sex.

The WSPU under the leadership of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst remained vehemently opposed to universal suffrage to the end. One can understand their reasoning. Emmeline understood – rightly – that acquiring the vote for working class men would be far harder than getting pledges of support for the enfranchisement of ‘respectable’ women on the same terms that men already enjoyed. Indeed, in regard to the latter, no persuasion was necessary – there was already a majority. Pankhurst wrote, Ref.[14],

“while a large majority of members of the House of Commons were pledged to support a Bill giving women equal franchise rights with men, it was doubtful whether a majority could be relied upon to support a Bill giving adult suffrage, even to men.”

What Mrs Pankhurst failed to appreciate was that the support for women’s suffrage in principle would never be translated into enfranchisement in practice unless the harder issue of full manhood suffrage were also achieved. As late as 1914 Emmeline Pankhurst wrote,

“Universal suffrage in a country where women are in a majority of one million is not likely to happen in the lifetime of any reader of this volume” (Ref.[15])

But Mrs Pankhurst failed to anticipate that the War would change everything.

Not all factions within the women’s suffrage movement were so resistant to universalism. The women’s movement was itself increasingly fracturing along two further fault lines: the use of violence, and the adoption of universalism. As for the former, the great mass of the women’s movement disapproved of the militant wing. This, the larger faction, were, in truth, of far greater importance than the militants, though the militants have grabbed the headlines.

It was not only the WSPU which held to the restricted objective of enfranchising only the ‘more respectable’ women. Millicent Fawcett, leader of the NUWSS, was initially no wiser than Mrs Pankhurst in appreciating that universalism was the only means of defeating The Big Snag. As late as 1909 Fawcett wrote, Ref.[16],

“I do not believe there is much genuine demand for universal suffrage. I certainly have not met with it when I have been about the country speaking….In any case our position is clear. We have nothing to do, and can have nothing to do, with a general alteration of the franchise as it affects men….Any change in the direction of adult manhood suffrage would make our task infinitely more difficult of attainment”

Like Mrs Pankhurst, Mrs Fawcett was both right and wrong: right that the enfranchisement of working class men was the more difficult task, but wrong in failing to understand there was no alternative but to tackle it – even if your objective was the vote for women.

In 1909 Fawcett was out of step with many in her own movement – but, unlike Mrs Pankhurst, Fawcett would eventually come round to the idea of universalism. In 1909 some of the non-militant suffragists formed the People’s Suffragist Federation (the PSF) to press the case for universalism – effectively a joining together of the men’s and women’s causes. The PSF, founded by Margaret Llewelyn Davies and others, drew membership from the parliamentary Labour Party and ‘universalist’ Liberal members. Even at that late stage, many women suffragists were sceptical; the WSPU openly hostile. But for an increasing number, this democratic initiative, in overcoming the class issue, simultaneously led to the uniting of the sexes in common purpose.

Margaret Llewelyn Davies in a letter to The Common Cause wrote, Ref.[17],

“Those who have initiated this joint movement of men and women (i.e., the PSF) believe that the effective political strength and the fighting force of the women’s suffrage movement will be greatly strengthened by showing that it is in harmony with democratic sentiment…..the democratic demand that suffrage should be placed on a human and not a property basis is the way to secure the passing of a great Reform Bill.”

“The PSF is not just playing men’s games with blindfolded eyes. If its women members want manhood as well as womanhood suffrage, they strengthen their demand for the vote for themselves, because the argument for Adult Suffrage is comprehensive and inspiring.”

The renewed vigour behind manhood suffrage was happening in the context of the Great Unrest. The period from about 1910 to 1914 saw an unprecedented number of strikes. There was more strike action in that period than at any time before or since. As far as manhood suffrage was concerned, this was not merely the politics of theoretical democracy but the realpolitik of strikes, civil unrest and the growing use of state military reaction. It was not only the women’s movement that had its militant wing, far from it. And it is worth considering the likely impact of the Great Unrest on the political mind just a few years later when the debates leading to the 1918 Act were being held in Parliament.

Now, finally, we come to the great unification of the two campaigns, men and women united in common cause. But it happened only very late in the day, in 1912.

As the suffragettes reached the zenith of their terrorist campaign, they simultaneously became irrelevant – except as a liability. By 1912 the alliance between the bulk of the female suffrage movement and the male-led labour movement, for so long resisted by both parties, became the main game in town. On 30th April 1912 a meeting was held between NUWSS officers and a subcommittee of the Labour Party which included Keir Hardie, Ramsay MacDonald and the Labour chief whip George Roberts. The latter confirmed that women’s suffrage was now Labour Party policy and that Labour remained pledged also to adult suffrage.

In 1913 the TUC and the Miners’ Union came on board to support female suffrage as their official policy. The Common Cause declared, “the question of the vote is no longer a question of sex. Cabinet Ministers who delude themselves with this belief – if any exist – are lamentably out of touch with public feeling, and particularly with the labour movement”, Ref.[18]. Sandra Stanley Holton, Ref.[19], opines that with this move the democratic women suffragists sought to offer an alternative to the sex war attitudes increasingly fostered by the WSPU leadership.

And so we come to the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914. This was a most effective cure for men’s militancy. Or, rather, their militancy became directed elsewhere, overseas. The WSPU ceased their suffrage campaigning in favour of addressing recruiting drives and urging men to go to war. In truth, the WSPU were already politically irrelevant – in fact, a liability to the new democratic impetus.

However, the non-militant, and now predominantly democratic, women’s movement continued to be active in the early years of the war. The NUWSS approach was now to stress the alliance of the women’s-suffrage cause with that of democracy, using this strategy as a means to intimidate Liberal leaders with evidence of working-class backing for their own demand. Quoting Holton, Ref.[20], “The Common Cause felt able to declare that the issue was at last being seen as a question, not of sex, but of democracy”.

I trust I have made that point emphatically enough!

Why was universal male suffrage and the vote for the majority of women achieved in 1918, with WW1 still in progress? The Government was fully occupied with prosecuting the War. To pass such a momentous Bill at such a time, Parliament must have had an equally momentous reason. The reason breaks down into two parts: the reason why it was necessary to re-examine the basis of the franchise at all, and, the reason why it took the form that it did.

The first of these is easy and provides a link with the war which is beyond any doubt. The electoral roll had been shot to pieces by the war. Millions of men were away at war. How could a franchise based on residency work under this conditions? Back home, the mobilisation of the entire country on a war footing had led to wholesale dislocations of people from their home towns and counties. The franchise based on household occupation was clearly invalidated under these conditions. There could be no general election whilst the war persisted, but the ground needed to be prepared to permit an election as soon as possible thereafter. Exactly who could vote – and where – needed to be sorted out.

The second question – why the new franchise took the form that it did – is the more interesting. To address the problem of how the franchise was to be redefined, the Government appointed a committee chaired by the Speaker of the House of Commons, called the Speaker’s Conference.

The Speaker’s Conference addressed the male franchise first. The principle of basing the franchise on the democratic basis of a personal right was established in that context. Only then was the issue of women’s suffrage addressed. The door was now open. They voted 15 to 6 in favour of making some sort of concession. In fact the Conference only very narrowly rejected an equal franchise with men, by 12 to 10. They explicitly did so in order to avoid creating a female majority. Instead they recommended an age restriction which was chosen to make the numbers more closely equal, though their estimate was not accurate. Without an age restriction, women would have entered the electorate for the first time with an immediate majority of 2 million. As it was, in 1918 they became 40% of the electorate.

The Bill passed its second reading in the Commons on 23rd May 1917 by 329 votes to 40. On a free vote on 19th June 1917, the Commons approved the women’s clause by 387 to 57 votes. It was subsequently passed by the House of Lords – which had previously been opposed to franchise increases – by 134 to 71 votes.

After decades of failed attempts to extend the franchise, to women or to more working class men, the 1918 Act sailed through to Royal Assent with stomping majorities for all parts in both Houses. How come? What had changed?

The answer, of course, is that the war changed everything.

The Home Secretary, George Cave (Conservative) introduced the Bill as follows:

“War by all classes of our countrymen has brought us nearer together, has opened men’s eyes, and removed misunderstandings on all sides. It has made it, I think, impossible that ever again, at all events in the lifetime of the present generation, there should be a revival of the old class feeling which was responsible for so much, and, among other things, for the exclusion for a period, of so many of our population from the class of electors. I think I need say no more to justify this extension of the franchise.” (Ref.[21])

So there we have it. The principle purpose for the 1918 Act was the need to dissolve the previous class-based franchise – and the specific motivation was the recognition that “if they are fit to fight they are fit to vote“, an actual quote from the Hansard record. It captures the prevailing sentiment precisely.

The primary motivation for the 1918 Act was men. The former opposition to the enfranchisement of working class men had evaporated as a result of the war. The age-old class antagonism could no longer be a barrier to recognising the equal rights of all men to political representation. To withhold the vote from men returning from years of witnessing appalling slaughter in the trenches was insupportable.

The debt owed to the soldiers and sailors is readily appreciated. But once the vote is given to these men, the entire class basis of the franchise collapses.

So, why were women enfranchised in the same 1918 Act? The reason why women received the vote alongside working men, in the same 1918 Act was simply that there was no longer any reason why not. It’s that simple.

Recall that Mrs Fawcett and Mrs Pankhurst both recognised that there had been a majority in Parliamentary for female enfranchisement since about 1884. The correct question, therefore, is not why were women enfranchised in 1918 but why they had not been enfranchised earlier? The answer to this is the Big Snag. With the Big Snag unsnagged by the wave of democratic sentiment due to the war, with the harder task of enfranchising working class men now accomplished, the vote for women simply followed as a virtually automatic consequence.

In short, women got the vote in 1918 as a collateral effect of working men getting the vote, which in turn resulted from the war.

The 1918 Act was the triumph of the principle of democracy, the vote being recognised as a right rather than being tied to wealth or property. That is what should primarily be remembered and celebrated.

Modern discourse fails to acknowledge the role of the war in bringing this about.

The 1918 Act was by far the most significant Act in the history of extending the franchise. It brought 13.7 million additional people onto the electoral register (5.2 million men and 8.5 million women). No previous Act had enfranchised more than 2 million.

It would be only ten years before women got the vote on the same terms as men, i.e., at 21. Women then became 54% of the electorate. Women have been the majority of the electorate ever since.

It is worth contemplating that there was only a ten year period in the entirety of history – between 1918 and 1928 – in which all adult men had the vote and the number of men with the vote exceeded the number of women. Men achieved full adult suffrage only ten years before women.

It was the slaughter in the trenches that gave birth to the new mood of egalitarianism in Parliament, sweeping away the old class based objections to enfranchising working class men. Consequently, one could say that the vote for working class men – and hence indirectly the vote for women – were bought with men’s lives. The popular historical narrative draws a veil over this ugly truth.

And yet it is surely a noble and uplifting thing, and I can think of little more genuinely worthy of celebration, than the fact that such a desirable, egalitarian advance – the triumph of the democratic principle – the triumph of the individual over a mistrusting elite – arose from the horror of the trenches. But that is forgotten. It has been eclipsed by the identity-group perspective of the suffragette mythology. We are ostensibly celebrating the 1918 Act, but in reality we are participating in neglecting its true significance. Just how disturbed should we be that, not only is the triumph of the democratic principle now deemed unworthy of note, but the crucial role of men in bringing democracy about has been replaced by such a divisive tale – so contrary to the true history.

Thank you for your attention.

References

Listed by number in order of appearance. In brackets is given the time in the speech the quote is made. Web links provided where available.

[1] (5.16) Sean Lang “Parliamentary Reform 1785-1928“, (Routledge 1999)

[2] (12.16) J.F.C.Harrison “The Common People: A History from the Norman Conquest to the Present” (Flamingo, 15th March1984)

[3] (19.22) House of Commons Library, “The History of the Parliamentary Franchise”, by Neil Johnston, RESEARCH PAPER 13/14, 1st March 2013.

[4] (19.30) Millicent Garrett Fawcett, “Women’s Suffrage : a Short History of a Great Movement”, TC & EC Jack, London, 1912, ISBN 0-9542632-4-3. Gutenberg online ebook here.

[5] (24.27) Benjamin Disraeli, introducing the Representation of the People Bill 1867, Hansard Volume 186, 18th March 1867.

[6] (31.36) ibid Ref.[4].

[7] (31.48) Emmeline Pankhurst “My Own Story” (Everleigh Nash, London, 1914). Gutenberg online ebook available here.

[8] (35.36) John Stuart Mill quoted by Charles Bradlaugh in [9].

[9] (36.09) Charles Bradlaugh in “The Real Representation of the People”, (printed by Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, 1884). Available online at the Charles Bradlaugh society here.

[10] (36.37) ibid Ref.[9].

[11] (37.35) ibid Ref.[4].

[12] Dawn Langan Teele, “Forging the Franchise: The Political Origins of the Women’s Vote”, Princeton University Press (16 Oct. 2018). See also “Ordinary Democratization: The Electoral Strategy That Won British Women the Vote” by Dawn Langan Teele, Politics & Society 2014, Vol. 42(4) 537 –561, DOI: 10.1177/0032329214547343

[13] (44.11) ibid Ref.[7].

[14] (48.58) ibid Ref.[7].

[15] (49.37) ibid Ref.[7].

[16] (50.57) Millicent Garrett Fawcett, letter to Marion Phillips, 12 September 1909. (Quoted in Ref.[18], chapter 3).

[17] (53.31) Margaret Llewelyn Davies in The Common Cause, 21st October 1909 and 11th November 1909 (quoted in Ref.[18], chapter 3).

[18] (58.00) Sandra Stanley Holton, “Feminism and Democracy: Women’s Suffrage and Reform Politics in Britain, 1900 – 1918”, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

[19] (58.18) Ibid Ref.[18].

[20] (59.34) Ibid Ref.[18].

[21] (1.04.48) George Cave (Conservative Home Secretary), quoted by Neil Lyndon in The Telegraph 6/2/18