The data below on deaths during, or following, police contact in England and Wales have been taken from the report by the Independent Office for Police Conduct, and relates to 2017/18.

The death statistics are broken down into five categories,

- Road traffic fatalities;

- Fatal shootings;

- Deaths in , or following, police custody;

- Apparent suicides following police custody;

- Other deaths following police contact.

Road traffic fatalities relate to the deaths of motorists, cyclists or pedestrians arising from police pursuits or from police vehicles responding to emergency calls, etc. It does not include deaths in other traffic incidents which the police attend but were not involved in the incident.

Fatal shootings relate to deaths caused by a police office firing the fatal shot(s).

Deaths in, or following, police custody include deaths that happen while a person is being arrested or taken into detention. It includes deaths of people who have been detained by police under the Mental Health Act. It includes deaths that happen following police custody where the injuries that contributed to the death happened during the period of detention. It also includes deaths as a result of medical problems while a person is in custody.

The category “apparent suicides” refers to apparent suicides that happen within two days of release from police custody, and possibly beyond that time if custody is believed to be relevant to the death.

The “other” category is expanded upon at greater length below. For now note that it is predominantly the first four categories, above, where there might be a concern over police culpability (brutality, neglect, lack of care, etc) whereas this is less likely in the “other” category. Consequently, I consider the first four categories first.

Table 1 disaggregates the deaths by sex and by the first four categories. There were 113 such deaths in all, of which 100 (88.5%) were of men. Easily the largest category was suicides. No women were subject to fatal shootings.

Table 1: Type of death by gender, 2017/18 (first four categories)

| Sex | Road traffic incident | Fatal shootings | Deaths in or following police custody | Apparent suicides following custody |

| male | 20 | 4 | 21 | 55 |

| female | 9 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| total | 29 | 4 | 23 | 57 |

Table 2 disaggregates the deaths by ethnicity and by the first four categories. Of the 113 such deaths, 89 (78.8%%) were of White people, 13 (11.5%) were of Black people, 8 (7.1%) were Asian, and 3 (2.6%) were of mixed race/other.

These figures compare with the general population which is 86.0% White, 3.3% Black, 7.5% Asian and 3.2% mixed/other. Hence, Asians and mixed/other races are represented in the police death data roughly in line with their prevalence in the population as a whole, whereas Black people (i.e., essentially Black men) are overrepresented. However, the statistics are small. No Black people were subject to fatal police shootings in 2017/18.

Table 2: Type of death by ethnicity, 2017/18 (first four categories)

| Ethnicity | Road traffic incident | Fatal shootings | Deaths in or following police custody | Apparent suicides following custody |

| White | 25 | 1 | 16 | 47 |

| Black | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Asian | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Mixed | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 29 | 4 | 23 | 57 |

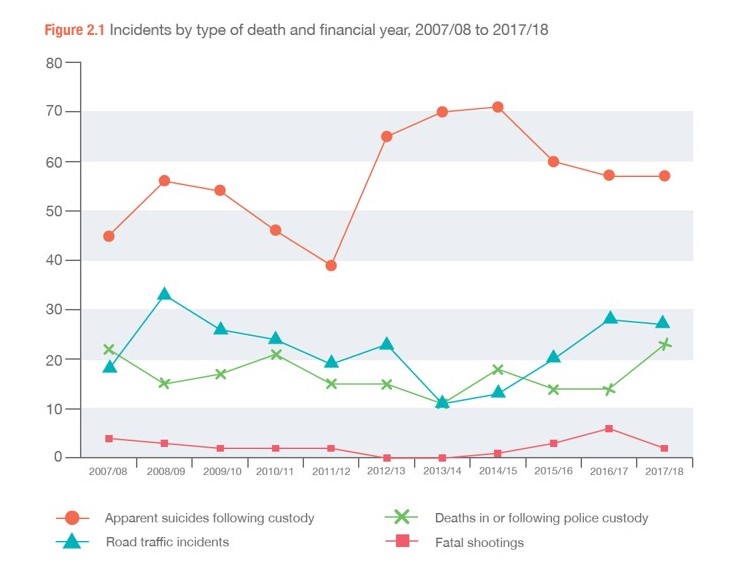

The Figure which heads this article puts in context the low numbers of fatal shootings by the police in England and Wales, especially compared with suicides following police contact.

Fatal Police Shootings

Between 2000 and February 2020 there were 55 recorded fatal police shootings in the UK (listed here). Reading the case summaries indicates the overwhelming majority of these police shootings were against armed men, or men who appeared to be armed or otherwise an immediate danger to others. There were, of course, mistakes – of which the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes was the worst. And the shooting of Mark Duggan sparked riots.

Judging from the names, ten of the 55 were Arabic/Muslim, perhaps 3 or so were European, and 42 had British names.

Just one of the 55 was a woman.

Including the “Other” Category

On average, the IOPC receive about 430 referrals each year where someone has died following police contact. Only a proportion of these are subject to independent investigation. This proportion was ~10% up to 2014/15, but has increased to about 40% (170) in 2017/18.

Of these 170 fatalities, 112 were men and 58 were women.

Of these 170 deaths, 146 involved calls to the police due to concerns for the subject’s welfare. Some involved missing persons, with whom the police had no direct contact. Over half the people who died (93) were reported to be intoxicated by drugs or alcohol at the time of the incident, or were addicts. Almost three-quarters of the people who died (120) were reported to have mental health concerns. In 27 of these incidents, the person’s death was from an apparent self-inflicted act.

Twenty-one of these fatalities were related to the police responding to a domestic incident. In this category twelve people who died were women and nine were men.

The remaining 24 deaths occurred whilst police were executing a search or arrest warrant or conducting an investigation, or assisting medical staff, or attending a disturbance. In this group there were 13 deaths after or during contact with the police who were executing a search, or an arrest warrant, or conducting investigation enquiries. All, but one, who was Asian, were White. All were men. In 11 incidents, the death was self-inflicted. In 12 of the 13 deaths, the police were making investigation enquiries, or following-up breach of bail conditions linked to allegations of sexual-related offences. Of the remaining 11, at least 2 were also self-inflicted.

Consequently, of the 170 “other” deaths, at least 40 were self-inflicted, in addition to the 57 suicides noted in Table 1.

Table 3: Type of death by gender, 2017/18 (all categories)

| Categories 1 to 4 | “Other” category | |

| male | 100 | 112 |

| female | 13 | 58 |

| total | 113 | 170 |

Table 4 disaggregates all deaths investigated by ethnicity. Of the 276 deaths where ethnicity was recorded, 237 (85.9%) were of White people, 17 (6.2%) were of Black people, 16 (5.8%) were Asian, and 6 (2.1%) were of mixed race/other (i.e., 14.1% were non-White).

These figures compare with the general population which is 86.0% White, 3.3% Black, 7.5% Asian and 3.2% mixed/other (i.e., 14.0% are non-White). Blacks are slightly over-represented in the fatalities, though non-Whites overall align with the population average.

Table 4: Type of death by ethnicity, 2017/18 (first four categories)

| Ethnicity | Categories 1 to 4 | “Other” category | Totals |

| White | 89 | 148 | 237 |

| Black | 13 | 4 | 17 |

| Asian | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| Mixed | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Unknown | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 113 | 170 | 283 |

Conclusion

The blindingly obvious demographic skew in fatalities associated with police contact is in relation to sex: namely, being male. This is especially the case where police culpability is more likely (the first four categories, above) for which 88.5% of the fatalities were men in 2017/18.

There is also a skew towards Black people, though to a far lesser extent than to men, and this skew vanishes for all non-Whites when all investigated fatalities are considered.

The context of this post is, of course, the wicked stirring up of racial tensions by parties with their own reprehensible agenda, using the death of George Floyd to inflame popular rage. Here is another video for you, from 2010. This shows a woman police officer needlessly tasering a man who has already been restrained by a group of male officers and is already on the ground. He did not die, and he did receive substantial compensation (which rather confirms that the force used was excessive). Regardless of the sex of the police officer, the sex of the person subject to treatment like this is almost always male – and, let us not forget, overwhelmingly most often White.