Here I look briefly at Type 2 paternity fraud and what should be done about men’s paternity rights.

Type 2 paternity fraud is when a man is tricked into fathering a child against his wishes. Unlike Type 1 paternity fraud, the child is genuinely his – he just didn’t want it. Perhaps the most common means of perpetrating this fraud is when the woman accidentally-on-purpose stops taking the pill and forgets to mention it. But there are other, more devious, ways. All of them depend upon the man trusting the woman with contraception, a state of mind which Janet Bloomfield has described as idiocy.

In addition to the simplest, and probably the commonest method of becoming pregnant fraudulently – sneakily stopping taking the pill – there are many other methods. Women will inseminate themselves from a used condom. They will poke holes in condoms. They will give a man a hand job specifically to get hold of some semen – and they don’t just wash their hands in the bathroom afterwards. They will buy fake pills to con the man, making a big thing of actually taking them in front of him. They will poke their arm and claim they have had a contraception jab. They will secretly have hormone injections to increase their fertility. They will pick up a man for a one night stand specifically to get pregnant.

Where am I getting all this from? From women, of course, such as Janet Bloomfield and Liz Jones. Here are some extracts from Liz Jones’s own confession (The Mail on Sunday, 3 November 2011),

Because he wouldn’t give me what I wanted, I decided to steal it from him. I resolved to steal his sperm from him in the middle of the night. I thought it was my right, given that he was living with me and I had bought him many, many M&S ready meals. The ‘theft’ itself was alarmingly easy to carry out. One night, after sex, I took the used condom and, in the privacy of the bathroom, I did what I had to do. Bingo. I don’t understand why more men aren’t wise to this risk – maybe sex addles their brain. So let me offer a warning to men wishing to avoid any chance of unwanted fatherhood: if a woman disappears to the loo immediately after sex, I suggest you find out exactly what she is up to.

And she further advises,

Any man who moves in with a woman in her late 30s or early 40s should take it as read that she will want to use them to procreate, by fair means or foul, no matter how much she protests otherwise.

She quotes what other women have confessed to her,

Many girlfriends have told me how they have tricked their boyfriend or fiancé or husband. One found herself childless in her 40s, so she lied to a very new boyfriend that she was on the Pill. He is now in a new relationship having to pay support for a child he never sees.

And the lengths these women are willing to go to make my half-baked attempts seem amateur. One tells me she used secret hormone injections to make herself more fertile; another uses a clandestine ovulating chart kept in the tea towel drawer (a place she knows her husband never looks in). I spoke to another friend over the summer who told me she was trying to get pregnant with her fiancé. She said: ‘I really want a year off work. I might even go part-time after that, maybe two days a week. He will just have to work harder.’

How common is all this? No one knows. By its nature, there are little in the way of reliable data. But Liz Jones says this,

A 2001 survey revealed that 42 per cent of women would lie about using contraception in order to get pregnant in spite of their partners’ wishes.

The root cause of the issue is that many (most?) women just do not regard paternity fraud as being wrong. This attitude is exemplified by one Jody, quoted by Janet Bloomfield,

“It’s not about trapping the guy,” Jody says.

Yes it is, Jody.

“Yeah, you want him to be into it, but there are other ways to get a guy to commit. If you’re smart and in a good relationship, it’s just about the fact that you want a kid.”

Indeed, it’s just about the fact that you want a kid – quite. It continues,

…this particular brand of subterfuge isn’t exactly condemned the way one might expect. In fact, it’s sort of, well, normal. “I see and hear people talk about it, and I understand. I get it,” she says, “and I don’t even think it’s that manipulative. It’s more like, Hey, the timing is right for me. I got pregnant—oops! Well, it’s here, let’s have it.”

The fact that you don’t think that fraud on such an important matter is manipulative is the problem, Jody. The fact that you don’t consider men to have rights is the bedrock of male disadvantage.

If the 42% figure quoted by Liz Jones is indicative of the frequency of Type 2 paternity fraud, when this is added to Type 1 paternity fraud, the conclusion is that more than half of children might be the result of paternity fraud. What should be done to establish men’s paternity rights, currently being so flagrantly violated? My personal opinion is as follows.

It is a woman’s right to choose. In other words, the established ready availability of abortion should continue, including the current safeguards in terms of timescale, etc. Some people have a moral objection to abortion. I respect that opinion as a moral position. However, my personal view is that abortion, within the established framework, is a lesser evil than bringing an unwanted baby into the world. (I do not, like Jessica Valenti, think that abortion should be permitted without timescale limitation. This vile woman wants women to be able to abort the day before the baby is due – a licence for homicide). If abortion is to be available, then it can only be the woman who chooses. There is no alternative, in my view. It is clearly insupportable to force an abortion on a woman who does not want one. It is equally insupportable to oblige the woman to bring an unwanted child to full term if abortion is available and sanctioned. It cannot be for the man in question to make this decision.

But where does that leave the man? At present it leaves the man as having no say whether his own progeny lives or dies. This, as I see it, is the de facto position that should not be altered. But this massive hole in male rights should be offset by other rights. It is wholly wrong for a man to have paternal responsibility forced on him for a child he did not want.

My proposal is the following seven points,

Paternal responsibility and paternal rights would be linked in law. This would have implications not just at childbirth but also upon divorce. Any responsibility to pay child maintenance would be linked to rights of access, probably in the form of equal shared parenting.

The adoption of paternal responsibility/rights would be voluntary on the part of the man if the couple were unmarried.

Paternity responsibility/rights would be an obligation upon the husband of the mother subject to DNA paternity testing confirming him to be the biological father.

All babies for whom any man wishes to be considered as having paternity responsibility/rights must in law be subject to DNA paternity testing prior to paternity responsibility being granted. Such testing will be obligatory for all children of a married woman (in order that the husband’s paternity obligation or otherwise may be decided). This requirement cannot be waived.

If a man is the biological father of the child, he will have the right to claim paternity responsibility whether married to the mother or not. The mother will not be able to prevent this.

A man not married to the mother will have no obligation to accept paternity whether he is the biological father or not.

If a man is not the biological father of the child, he will have the right, but not the obligation, to claim paternity responsibility only if the mother is in agreement – whether married or not. (If a man refuses to accept responsibility for another man’s child by his wife, he would have no obligation to support it financially. In practice, if the couple stayed together, this is unlikely to make a practical difference. However, at divorce, the woman would have no claim for child support and the man would have no claim for access/custody for the child in question).

These proposals are, in my view, as close to equitable as possible, given the natural skew on the matter imposed by biology. One of the objections that will be raised to these proposals is that “letting men get away with it” will lead to a dramatic increase in poor, single mothers having to cope alone. But this ignores the recent history. The epidemic of single motherhood has already happened. And it has happened whilst men were not “getting away with it” and whilst women, but not men, had virtually complete control over conception.

As they stand my proposals would be entirely unacceptable to those responsible for the nation’s budgets. The State’s priority is to ensure that as many children as possible are financially supported by a man – any man. My proposals would leave the tax payer exposed to a potentially increased burden from an increased number of single mothers without a male supporter. To be workable, my proposals would have to be matched by government determination to reduce the level of benefit support to single mothers.

At this point the howls of anguish will become truly deafening. How can the nation throw 2 million single mothers into penury? The answer is that the benefit changes would not be applied retrospectively – and the changes would be very well advertised. The result – should any government have the nerve – would be a dramatic, overnight drop in the rate of births to women who had not the financial means to raise a child – or the support of a committed man in that endeavour.

Faithful, married women would be secure under the above rules.

Of course, I am not such a fool as to imagine this will happen in the foreseeable future. Indeed it will never happen at all if the only arguments than can be brought to bear in its favour are equality, fairness and justice. Equality for women has provided a motivation for legislative change, but there is little hope that equality for men will ever do so. For these changes to come about, encouragement beyond mere arguments is required.

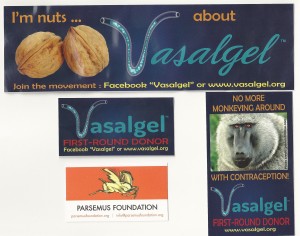

This is one idea which may encourage the powers that be…

(No, I don’t have shares in the company).

At present, fatherhood is a temporary status conferred on a man by the mother, a status which she can revoke at any time – and do so independently of his financial obligations. Since men cannot truly have children under the current arrangements, why cooperate with their conception? If a sufficient proportion of young men took the Vasalgel option (if and when it becomes available) it could have a forcing effect on the matter. If the birth rate dropped by 50% the government would have to respond to the impending demographic bombshell (tax revenues would drop dramatically but the national debt would not).